“A Most Regrettable Occurrence”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

July 2017

The Park season of 1924 witnessed a most regrettable occurrence in an outbreak of typhoid fever, wherein a number of cases were proved to have had their origin in the drinking of water from a brook flowing down the face of the Palisades. This brook had become contaminated through a break in a private sewer outside the Park, permitting raw sewage to overflow into a surface water drain, which in turn drained into the Park brook.…

With that short statement in their Annual Report, the Commissioners of the Palisades Interstate Park summed up a summer of woes. And it struck us, all these years later, as worth looking into some more, to see what it might tell us about the park’s early days, back when our brackish old Hudson was a much busier — and much dirtier river — and when most of our visitors came to this park not by car or by bike, but by ferryboat or canoe…

Frank Monaghan, M.D., Health Commissioner for the City of New York, had a mystery to solve. By mid-July, sixty-six cases of typhoid fever had popped up across the city: thirteen in the Bronx, a couple dozen or more each in Brooklyn and Manhattan, a single case in Queens. Then as now, typhoid was a disease that mostly afflicted children. Eight of the victims were under eleven years old; fifty were between the ages of twelve and sixteen; the remaining eight were between seventeen and twenty-two. It could take a week or more for symptoms to appear from the Salmonella strain that caused typhoid. What linked these scattered cases together?

It was an urgent question: four children so far were dead.

Dr. Monaghan found a clue with five boys from a Brooklyn “orphan asylum” who went on a hiking trip across the Hudson before they got ill. All five drank from a brook near where the Dyckman Street ferry landed them in the Palisades. Next he learned that a dozen Boy Scouts had drunk from that same brook — one was still in the hospital. When the brook was tested, the New York Times reported, “a culture of pure typhoid bacilli was obtained.” Dr. Monaghan issued a report on Tuesday, July 15. By that afternoon, the number of cases had risen to sixty-eight. More were coming.

It may be that sooner or later an outbreak was bound to occur. Two years before, in 1922, Englewood Hospital reported that a swimmer who swallowed river water at a park beach had come down with typhoid. Just one case. But the commissioners had ongoing concerns over sewage leaks from neighboring properties: from the Villa Richard hotel on top of the cliffs in Fort Lee, from “Camp Happy Days” and “Camp Idlewild” — a pair of privately run “automobile camps” just outside the park in Englewood Cliffs — even from the cliff-top convent run by the Sisters of Peace. (“I wish to call your attention to the break in the sewer pipe which runs over Park property,” the Commission’s secretary wrote the sisters back in 1909. “This must be fixed, and in attending to it we would like to have the pipe continued further in the River so that the refuse will be carried out beyond the low water mark” — and so swept away by the tides.) Earlier in 1924, the Commissioners had begun to send letters to officials in Englewood Cliffs about a private sewer used by some residents of the borough who lived at the top of Palisade Avenue, near the automobile camps. They feared a leak could pollute the brook that ran down the Palisades to Englewood Picnic Area, and which fed some springs there.

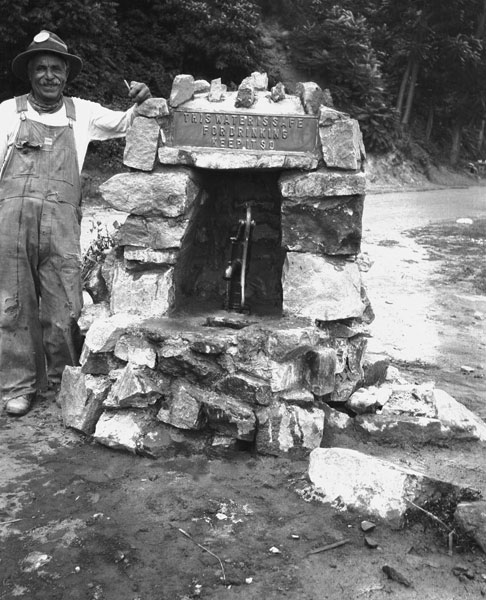

As far back as 1908, as they were first turning this “twelve miles of shore frontage, covered with thick woods” into a park, the Commissioners had noted the need to pay “particular attention … to protecting the water supply of the various springs.” These natural water sources, where rainwater flashed down gorges or percolated through soil and stone to seep back out at the base of the Palisades, would be the main source of fresh water for a generation of park visitors. But as a major ferry line began crossing from Dyckman Street in Manhattan to the park, and as they oversaw the construction of big stone bathhouses for the beaches at Fort Lee and at Englewood Cliffs, the commissioners realized that in that section of the park, a more permanent source of clean water was needed.

By 1924, the Bergen Evening Record reported, there were “several hydrants providing Hackensack [Water Company] water” in the park. Still, “the New York throngs seem to prefer the spring water, probably because of the suggestion that it might be colder than that from the hydrants…” That July, park workers drew up warning signs (literally: on an unpainted wooden plank, the Times noted, “a warning was written in a black grease pencil with the word ‘Typhoid’ in red…”), but visitors still used the springs. The problem, Herbert Jenkins, the mayor of Englewood Cliffs, told the Times, was that the signs were in English — he doubted many park visitors could read them. (The mayor also made sure to point out that responsibility for the crisis “rested with the Interstate Park Commission.”)

Dr. Monaghan’s report told how an inspector “saw one of a picnicking party wash melons that had been cut open … with water from a polluted spring, in spite of warning signs and verbal instructions. It required a lengthy talk to persuade the party to refrain from using the contaminated food…” The next weekend, the Times reported, dozens of guards were posted to warn visitors away from the springs, and “most of the pipes and outlets, which made natural drinking fountains, were plugged up or pulled out of the water … so that visitors had no chance, it was believed, of getting into trouble. Practically every spring between the Dyckman Street ferry house and Alpine, a distance of five miles, was closed against use.” Still, some fifty-thousand New Yorkers “swarmed over the danger zone … to enjoy Sunday in the cool country.” The next week “circulars [would] be printed in every language and distributed to persons going to the park, warning them against the polluted water.”

Whether the cause was the cesspool at Camp Idlewild, as Dr. Monaghan believed, or, as the Commissioners suspected, a leak from the residential sewer, the outbreak was halted by closing the springs. Over eighty cases, but the death toll held at four. Maybe they could breathe a sigh of relief?

But then came Edward Hatch Jr. — to announce that he planned to seek indictments against the Commissioners of the Interstate Park.

Employed at Lord & Taylor, the sixty-five-year-old Hatch had made a name for himself as a sanitation crusader. In the early 1900s, when he lived in Vermont, he led the campaign against pollution by pulp mills at Lake Champlain. Now he headed the “fly-fighting” committee of the American Civic Association and chaired the committee on pollution for the New York City Merchants’ Association. The author of numerous pamphlets on public health and sanitation over the years, he had even dabbled in early filmmaking as an advisor for 1910’s The Fly Pest, about the dangers of houseflies. And now typhoid was raging in the public park right across the river!

Hatch hired a couple of health inspectors to investigate conditions at the park. It couldn’t have helped his impression of park management that as soon as he got to the waterfront, one of his inspectors found a dead body. No matter that the body almost certainly had nothing to do with the typhoid outbreak (from his overalls and some papers in his pockets, the unidentified middle-aged man was most likely a boatman who drowned — somewhere on the river — a week or more before). What his inspectors had found, Hatch sputtered in a statement to the press, “was an unsanitary condition unthinkable at this stage of civilization. The water which hundreds of thousands of campers had been told was pure is filled with lusty bacilli. The bacilli have been thriving for years without any attempt of the Park Commission’s to stamp them out.…”

As far as we can tell, the indictments never came.

But enough was enough. Four children had died. Summer attendance in 1924 dropped by almost a hundred thousand visitors. Revenue was lost, and the park’s reputation as a healthful oasis had been hurt, badly. In December, as the commissioners prepared their annual budget, they added a request for $12,000 for a new pipeline. “In connection with the regrettable occurrence of last summer,” they wrote, “it has been borne in upon the Commissioners most forcibly that every brook and spring in the Park should be closed at once, against their use by the public, and fresh water piped into the [entire] Park from some pure source of supply…”

– Eric Nelsen –