Allison’s Will

A “Cliff Notes” Story

March 2011

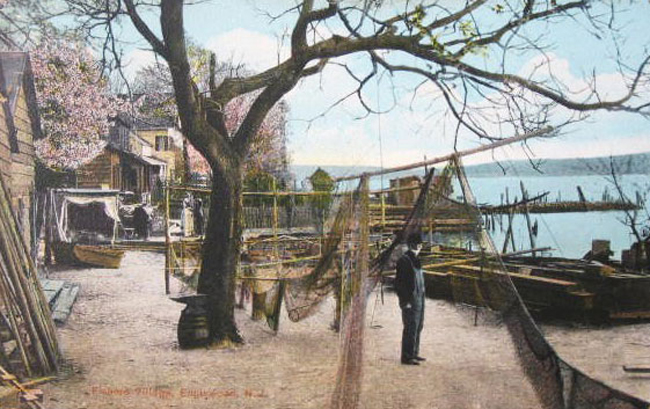

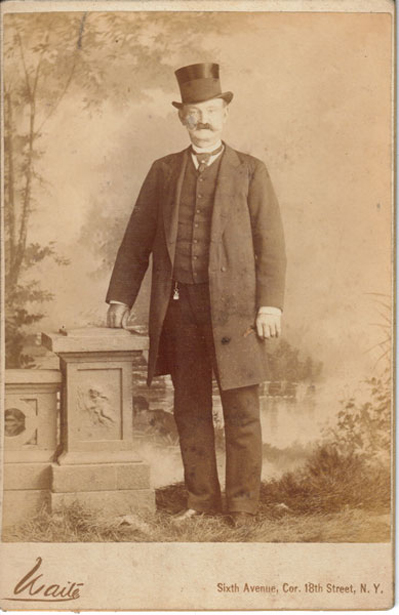

His doctor was pleased with his recovery from the pneumonia, but then came multiple thrombosis — a blood clot in his brain left him paralyzed — and two days later, early on Thursday morning, December 18, 1924, William O. Allison was pronounced dead at his apartment on West Sixteenth Street in the city. He was buried on Saturday at Brookside Cemetery in Englewood — just a morning’s walk, really, from the Hudson River hamlet where he’d been born seventy-five years before, a river man’s son. At his death his estate was worth over $3,000,000.

He was eleven in 1860 when the Danas built “Greycliffs” on the Palisades at Englewood. William Buck Dana published a financial journal in the city; Katherine Floyd Dana wrote short stories and poems. Devoutly religious, they opened their big stone house on the cliffs to the local children for Sunday school. Right off they saw something uncommon in Billy Allison: climbing the old wagon road with the fish he’d caught to sell them. The Danas — they had no children of their own — approached Billy’s father about adopting the boy (one story has it this was after he’d cut off part of a finger chopping wood for them). His father refused to allow his son to forsake the family name, but he agreed he could live with the Danas as their ward. So Billy Allison moved up the mountain for good. William Dana would take him to the city to teach him about publishing and business, while Katherine Dana schooled him in art and literature.

Years later he would still sign letters to them, “Billy.”

He was twenty-two in 1871, making his name as a sharp business reporter, when he founded the Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter, the first of the three trade journals he would publish. He would also sit on the boards of banks, invest in real estate and railroads, and buy a failing steamship company — to turn it around. He became the principal owner of the Palisades Mountain House, the grand cliff-edge hotel just south of Greycliffs (William Dana had been among its financiers) and was staying in it the night it burned in 1884. He’d build his own house on the ruins. He shared the fruit of his Jersey gardens with the employees at his office at 100 William Street, and he led botanical societies on tours of his Palisades estate.

He was forty-four in 1893 when he got into a hot dispute over an election in Englewood. After the dust had settled, in 1895, the easternmost section of Englewood had split off to become the Borough of Englewood Cliffs; he was elected the new town’s first mayor.

He felt a deep pride in his “Jersey Dutch” forebears, who had wrested their livelihoods from the river. He became a vice-president of the Bergen County Historical Society. With his sons he interviewed the now ancient-seeming river folk he’d known as a boy for a book he planned to write. (Much of this work was lost when the home he built on the Mountain House ruins itself burned in 1903.) He bought land on the Palisades by the hundreds of acres.

He married Caroline Hovey in 1884, and she bore him six children: a little boy and a baby girl were taken before Caroline’s own death in 1896; tuberculosis took another son, Van, in his twenties; Katherine, Frances, and John were still alive in 1924, as was Caroline Shaw Allison, his second wife, whom he’d married almost a year to the day after the first Caroline died — but from whom he soon separated. The four of them, the three children and the widow, would not be pleased to learn the contents of William Allison’s will.

“It is my desire and intention,” he stated in his will, “to dispose by gift of a large part of my remaining estate for the purpose of pleasing Almighty God, benefitting my fellow man, and as far as possible developing that section of the Palisades along the Hudson, located in the Borough of Englewood Cliffs and vicinity.” He named two close business associates, Harry J. Schnell and Frank V. Baldwin, as executors and “Trustees of the Trusts hereinafter created.” He made several bequests to longtime associates, but stated explicitly, “I have made no bequest … to my wife, children or grandchildren, for the reason that I have already made adequate provision for them” through trusts already established. Schnell and Baldwin were ordered to use the remainder of the estate “for the development and maintenance of said Palisades Section in accordance with my wishes as expressed to them.” He authorized the trustees to sell “any or all” of his properties to finance their efforts.

The lawsuits began. The plaintiffs presented affidavits that the old man had lost touch with reality; that he had been manipulated; that he had been sick, even depraved. The defendants countered with affidavits that William Allison had been keen of mind to the very end; a warm and caring friend; a benefactor. In 1926 a court set the will aside; it was reinstated on appeal in 1927. The value of the estate was said to have ballooned to over $8,000,000; or, it had plummeted with the stock market crash.

The lawsuits dragged on, into the 30’s, draining the trust.

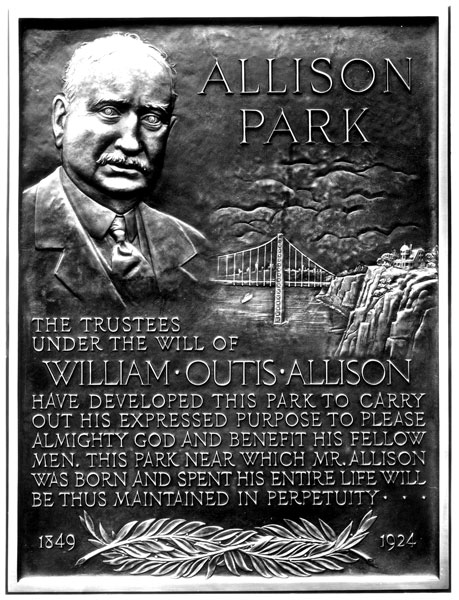

All the while, Schnell and Baldwin struggled to decode the intent of Allison’s will. They opened and maintained one section of his property — about eight acres on the cliff edge near where he’d actually lived — as a public overlook and park. They installed a handsome iron fence, built modern restrooms, hired a caretaker. They mounted a plaque honoring Allison. In court they produced affidavits that Allison had once envisioned a “super university” in Englewood Cliffs — and had invited Woodrow Wilson to head it after his presidency. Had he not also spoken of wanting to build housing for working families? …a hospital? …a museum?

By the time they beat back the last of the lawsuits, fewer than a hundred acres remained unsold from the trust; Schnell and Baldwin were growing old. New trustees were appointed; one of them — a former New Jersey Attorney General — was alleged after his death to have embezzled from the trust, badly. (In 1988 Flat Rock Brook Nature Center was awarded trusteeship of “Allison Woods Park,” a 75-acre tract along Jones Road in Englewood — and the last big piece of Allison land left unsold by the trust.)

In 1967 the struggling trust turned over the overlook park to the Palisades Interstate Park Commission: “Allison Park,” with its iron fence, its (now ancient-seeming) restrooms, its plaque from which William Allison seemed to stare with a strange, almost disturbing intensity — a son of the wild Palisades — a man of business — a private soul with public dreams.

– Eric Nelsen –