“Devil’s Heads”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

May 2004

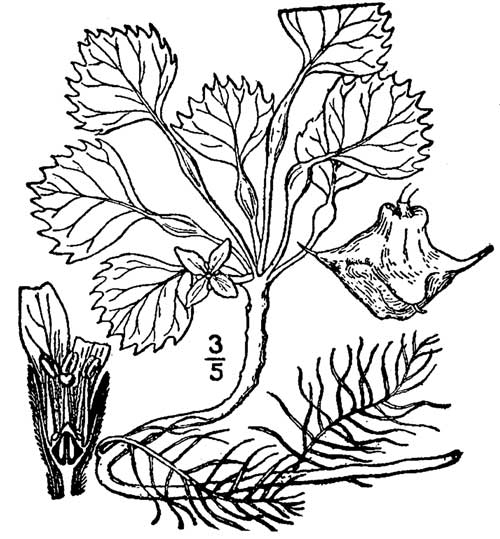

“A child said to me What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands,” Walt Whitman famously wrote in “Song of Myself.” Here in the park, when a child comes running up to us with hands full of something that needs explaining, as often as not it’s a handful of dark gray objects, each about an inch or two across with four curved, spike-like “horns” projecting from a knobby hub. The children find them — first one, then another, then dozens of them — as they explore the shoreline of the Hudson. Many people — including adults — when they examine one of the little gray knots of spikes for the first time puzzle over whether it is human-made or organic. The texture feels like plastic. More than one person has commented that it first seemed to be part of a broken action figure, a tiny Darth Vader helmet perhaps, or part of a model of the creature from the Alien movies. There is indeed something about them that suggests science fiction. And why not? These pods contain the life force of an alien invader.

“Devil’s Heads” some people call them, but more properly, they are the fruit of Trapa natans, a plant that has the common name water chestnut. The native range of T. natans is from western Europe and Africa to northeast Asia, including eastern Russia and China, and southeast Asia to Indonesia. In much of this range it is cultivated as a food crop, but it is not even in the same family as the “water chestnut” (Eleocharis dulcis) you can buy in cans at the market or that are used in Asian cuisines at restaurants in this part of the world. (Even where T. natans is cultivated, it is often regarded merely as a subsistence crop and not held in particularly high culinary regard.)

Probably around the 1870s, someone decided to bring some of the horned fruits to this country, perhaps thinking the plant would look nice in a neighborhood millpond.

He or she tossed a handful into the pond.

In the shallow water, a stem grew from the single seed each fruit contained. From a point on the stem, a circular group of leaves, called a rosette, grew outward. The leafstalks holding the rosette to the stem were made up of a spongy tissue that enabled the rosette to float to the surface of the water. In the leaf axils, flowers bloomed; a new crop of horned fruit began to grow there. As new rosettes grew along the stem and floated up, the older ones, with the developing fruit, got submerged (since the water was shallow, the submerged leaves could still contribute to the work of photosynthesis). When the fruit matured, it fell from the plant and sank to the bottom. The “horns” helped anchor the fruit against currents that might sweep it into deeper water. For four months or so the fruit remained dormant. Then a new stem emerged from each. Rising on a buoyant parasol of green leaves, the stem stretched for the sun.

In 1884, T. natans was observed to be growing “luxuriantly” in Sanders Lake at Schenectady, New York. Soon the plants were growing in other lakes and ponds; they found their way into rivers and canals, spreading their clusters of rosettes — the stems can grow up to 16 feet — across the Northeast. In many places, T. natans now covers acres of shallow water at a time and can be found as far north as Quebec and west to the Great Lakes Basin. Hundreds of thousands of dollars have been spent to eradicate, or at least to control, the plant. In Florida and South Carolina, you can get yourself arrested for trying to transport the plant or its seeds into or across the state, let alone planting the things.

Why the fuss? The problem with T. natans, like so many non-indigenous, “invasive” species, is that it’s simply too good at what it does. What it does is grow. And grow. And grow faster than most of the native plant species that occupy the same ecological niche. The rafts of leaves it spreads through the water block the sunlight the other plants need, spelling their doom (in that locale at least).

Like a robber baron of old, T. Natans monopolizes its niche.

There are economic costs, as well (in addition to the cost of trying to control it), some of these costs difficult to calculate. Activities like fishing, boating, and swimming are hindered by the rafts of rosettes — and waterfront businesses start to close their doors.

You won’t see T. natans growing along the Palisades. It needs fresh water, for one thing, not the brackish soup we have to offer. But upriver, a hundred miles or more, it thrives. Each year the current pushes its horned fruit by the thousands toward the sea. And each year, it seems to us, we notice more “Devil’s Heads” washed up on our shores than we did the year before.

– Eric Nelsen –