Fly Away

A “Cliff Notes” Story

May 2009

CAPE FLY-AWAY. A cloud-bank on the horizon, mistaken for land, which disappears as the ship advances. (See FOG.)

From The Sailor’s Word-book, Smyth and Belcher, London, 1867.

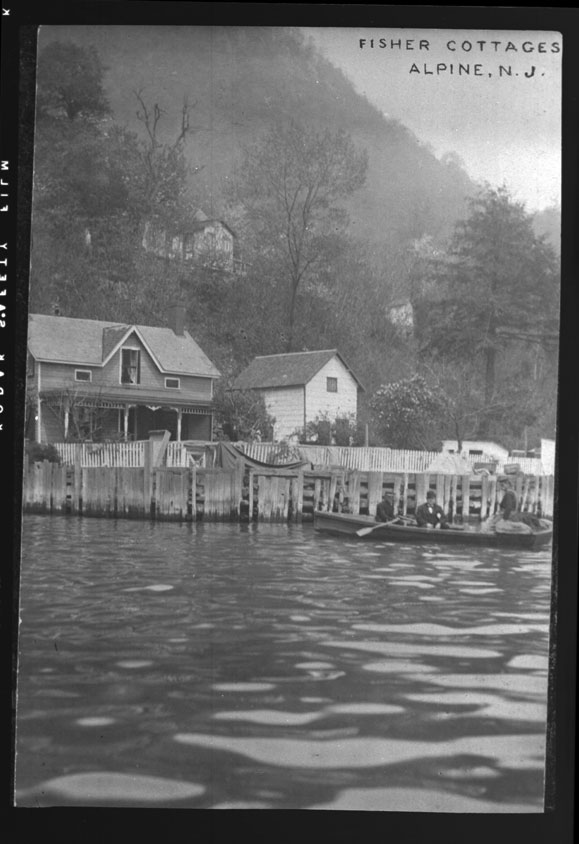

Not half a mile north of Alpine Landing was Cape Fly Away, with its pretty name and its long memories back to when Dave Van Valen and Matt Westervelt in the vigor and heady enthusiasm of youth (each had just married a Bogert girl — sisters — on the same Saturday at Schraalenburgh) piled stone upon stone to build terraces across the steep-as-a-roof slope between river and sheer cliff, and so brought a farm into being — a farm! Gil Kearney, John Jordan (there was always a Jordan in the story, then as now), Jake Coe: each of them, too, would marry a Bogert sister, each in his turn, and each of them gone now, all the sisters too. The Commissioners of the Interstate Park rented out the old houses for the summer, “cottages,” so folks from the city could flee the heat for cool river breezes. The docks grew more rickety with the years, and the farm with all that mad labor was long abandoned, the slope again tangled with wild vegetation. Yet there was a Jordan — of course — living at the Cape still: Gene, the bachelor, “retired” he told people, yet still fished the river with all his heart (as he would for two decades to come). Mrs. Quinn lived at the Cape still, too, Frank’s widow — from green Ireland they’d come, back in the sixties, and this was where they stopped the long moving on — with her grown son and grown daughter.

One by one over the years to come they would leave, each in his or her turn, but this was 1909 — the year the new park was to be dedicated (Mrs. Quinn’s Sam even worked for the Park Commission, as a boatman).

At the big docks at Alpine Landing meanwhile, Watson Wilkes, a steamboat pilot, and his wife Sarah and their three girls had been renting year-round at the old Kearney house (the one that was said — by some — to have been used by Lord Cornwallis in Revolutionary days) until in the spring they got the bad news: The Commissioners wrote to Watson Wilkes from their office in the city that they had plans for the house; he and his family would have to be elsewhere by July. (The plans, it turned out, were for the park’s dedication ceremony, which was to be held in September at “the old Cornwallis house” — the Commissioners, at least, seemed willing to buy the Cornwallis stuff. They hired a contractor, a local fellow named Sage — he’d married the daughter of both a Crum and, yes, a Jordan — to fix the place up. Herman Sage was to make the old house look “Colonial,” to hang some new windows and some Dutch doors, to give it a fresh coat of paint. And to build a big new porch to be a grandstand from which the governors of New York and New Jersey would address the crowds.)

Watson Wilkes and his wife and his girls moved to Manhattan, to a place on Eighth Avenue.

Alexander Campbell meanwhile had built his house just north of Alpine Landing, before Cape Fly Away but past where Colonel Miles’s steam-powered mill (closed now) grinded oatmeal and coffee the better part of this past half-century. Campbell had been one of the leaders in the dock-building business: he and his boys — and his nephews and grandsons — had hammered together the wooden stone slides down which workers (like Frank Quinn) had run the stone; they’d loaded that stone onto sloops and schooners that the Campbell family owned; they’d sailed that stone to South Street or to Gowanus or to wherever else there were men building docks for oceangoing vessels. Then, in ’01, seventy-seven years old, his stomach got knotted up and four days later Sandy Campbell was dead.

Eight years later still and his children were driving the Commissioners near to apoplexy.

The Campbell children happened to own the one piece of riverfront property near Alpine Landing that the Commissioners had yet to acquire. And the children didn’t want to sell it. Or they couldn’t agree on how to sell it; or for how much. One or two still lived nearby; another on Long Island; daughter Maria Campbell, now Mrs. Kearney, lived across the river at Yonkers with her Monte (Gil’s son — the son of one of those Bogert sisters). Mother Mary Campbell meanwhile — the widow, the former Mary Vansciver — still lived in the house on the river that Sandy built with his own two hands. The dedication loomed: the Commissioners wanted to have the land titles settled out, badly. At last they threatened condemnation; and made their final offer. If the children agreed to sell, they offered, their mother could stay until she died (she was very old). No rent would be charged.

And so the children sold, just days before the ceremony. And so Mrs. Campbell stayed (and stayed: till she died — almost twenty years later.)

The city folks came in the nice weather now, endless streams of them, nosing their canoes into the coves. Wondering who on earth still lived there — and why? They built their fires and cooked their lunches, made their coffee and went home. And sometimes the next morning, when the sun cleared the hills above Yonkers and the ancient wooded face of the Palisades — forever doomed to be described by poetical outsiders as aloof or impenetrable or brooding or some such nonsense — glowed golden from within like a treasure chest, for those few moments Cape Fly Away with its tired old houses and its forlorn docks would again be as pretty as its name.

– Eric Nelsen –