From the Hard Winter

A “Cliff Notes” Story

April 2014

The Civil Works Administration, or CWA, existed for exactly one season: winter. In the depths of the Great Depression, when unemployment rates stood as high as 25 percent, the CWA provided work for around four million men nationwide. The program expired after March 31, 1934 — it was to be a stopgap, not a permanent measure. A year later, the Roosevelt Administration created the more permanent Works Progress Administration, or WPA, which operated until 1943. Today, the WPA is far better remembered than its predecessor. Yet over that one season in the Palisades, the CWA left an impressive legacy.

CWA workers first reported to the park in December 1933. They came mostly from the towns just to the south, from Fort Lee or Cliffside or Fairview. On average, they were around five hundred men each day.

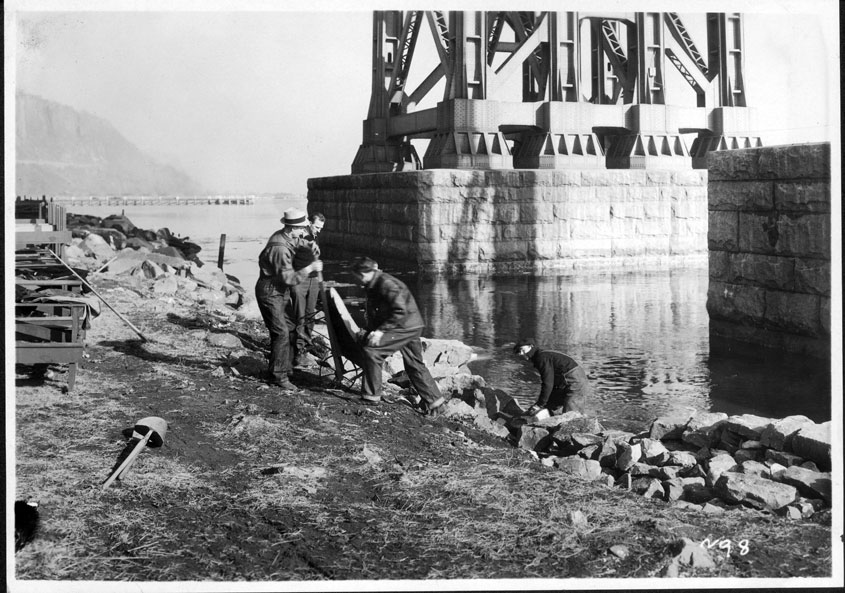

Their work spanned the park from Fort Lee to Alpine, most of it along the riverfront. They graded the new two-mile extension of Henry Hudson Drive southward from Englewood Picnic Area to the park’s new Edgewater entrance, and they painstakingly laid a cobblestone base on the new roadbed for paving. They built seawalls at Hazard’s Landing, just beneath the new George Washington Bridge, and at the Dyckman Street Ferry terminal. Throughout the park they built “additional fireplaces, paper burners, incinerators [and] other general improvements.”

Besides manual laborers and supervisors, twenty-seven CWA engineers were used by the Park Commission to survey the route of a newly proposed parkway on the summit of the Palisades. They produced “a full set of working plans, estimates, and specifications for the total length of the parkway from Fort Lee to the New York State line.”

Perhaps most ambitious of all, CWA surveyors staked out sites for two stone bathhouses, one at Alpine Beach in Alpine, another at Bloomer’s Beach in Englewood Cliffs.

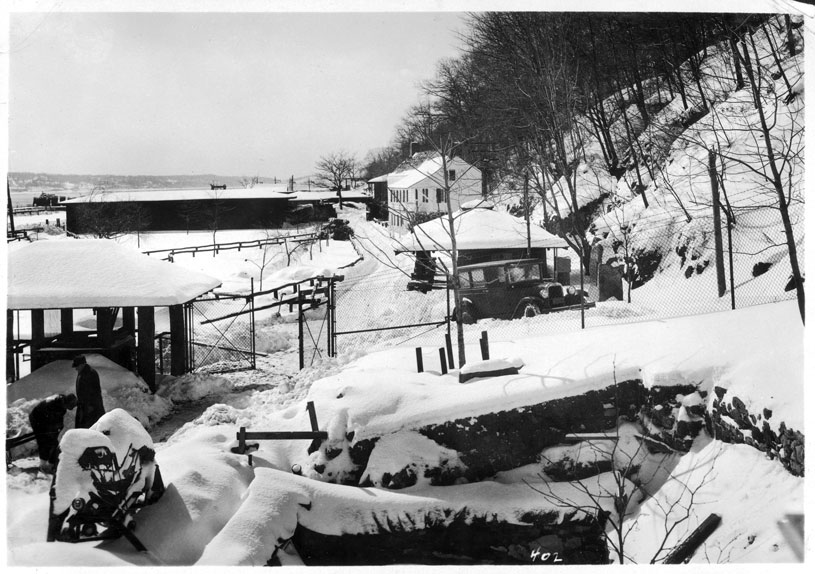

A snowstorm dumped almost a foot of snow late in December. But then temperatures moderated through January; once or twice the mercury even climbed into the low 50s. The snow vanished. CWA crews dug several miles of trenches to bury water lines below the frost level; they excavated an underpass beneath Henry Hudson Drive for the old Lambier trail in Tenafly; and they started building half a dozen new refreshment stands and entrance booths.

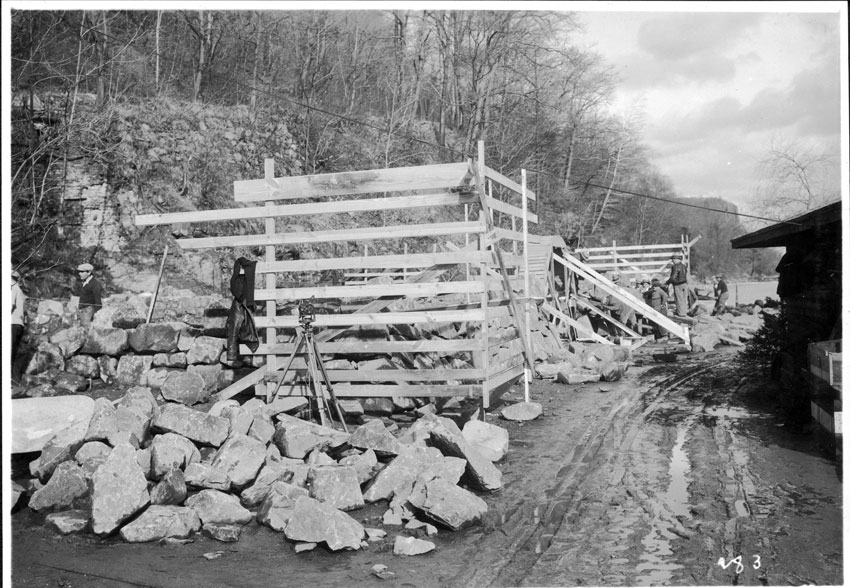

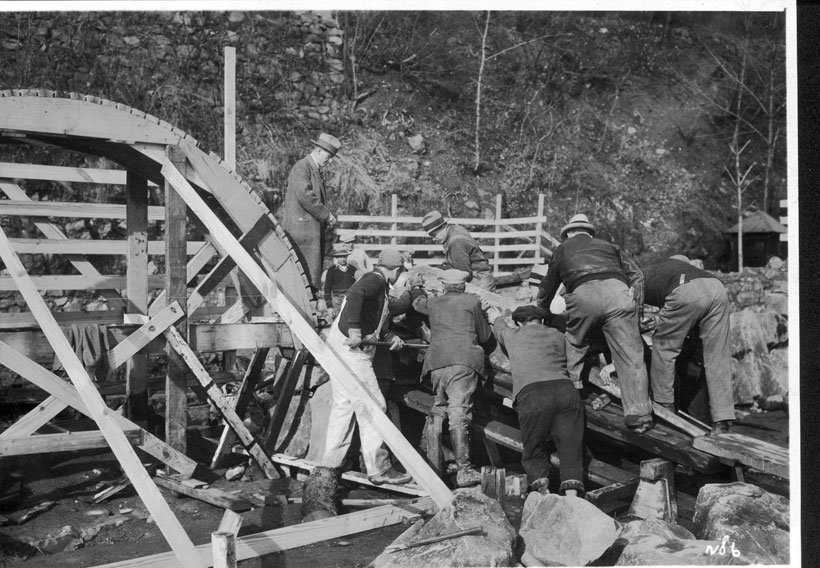

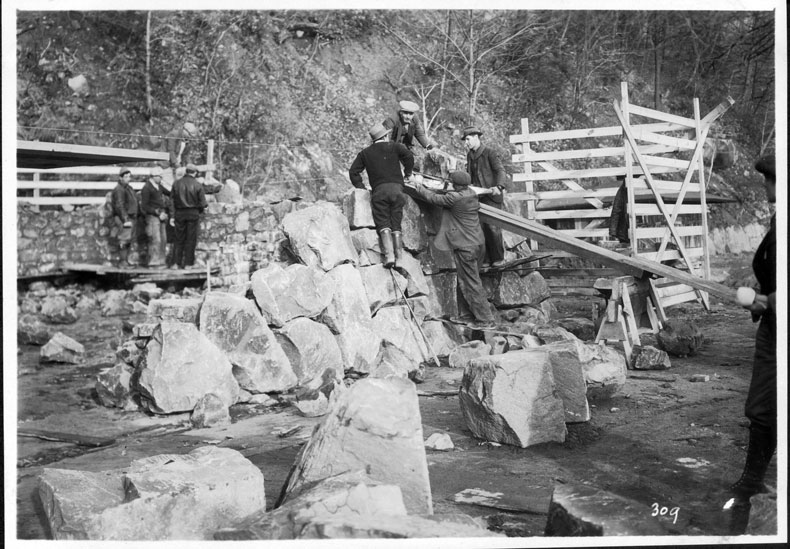

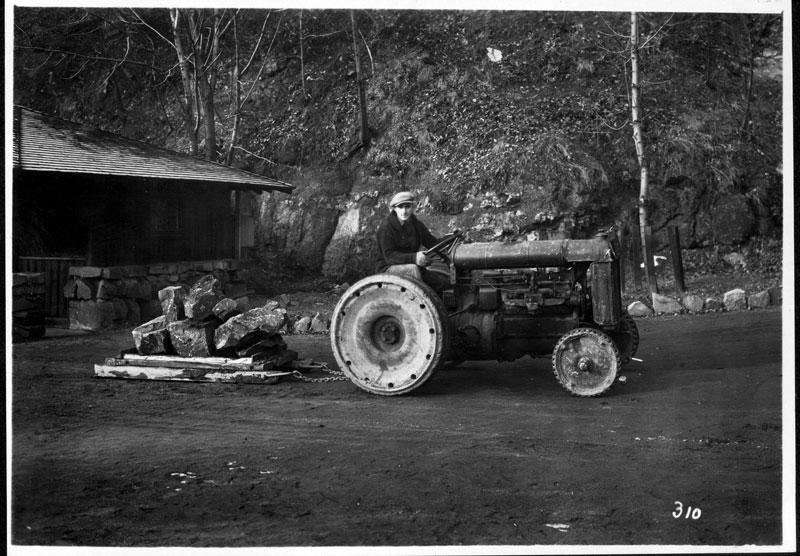

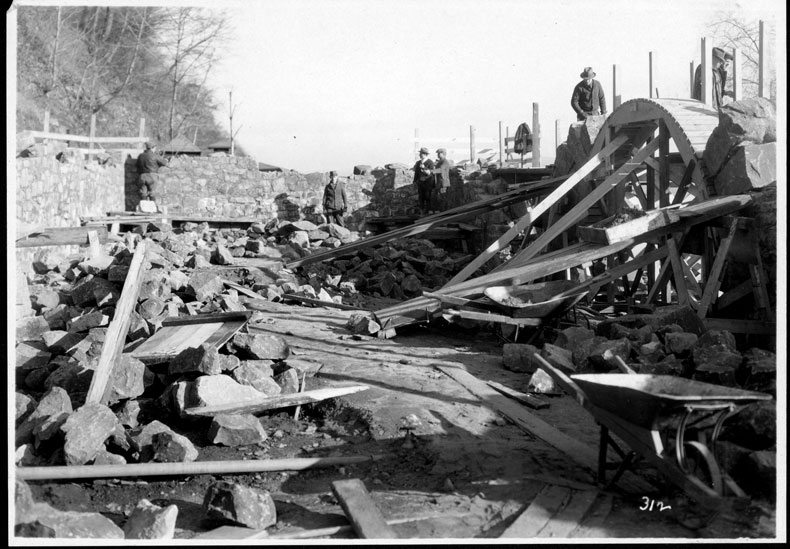

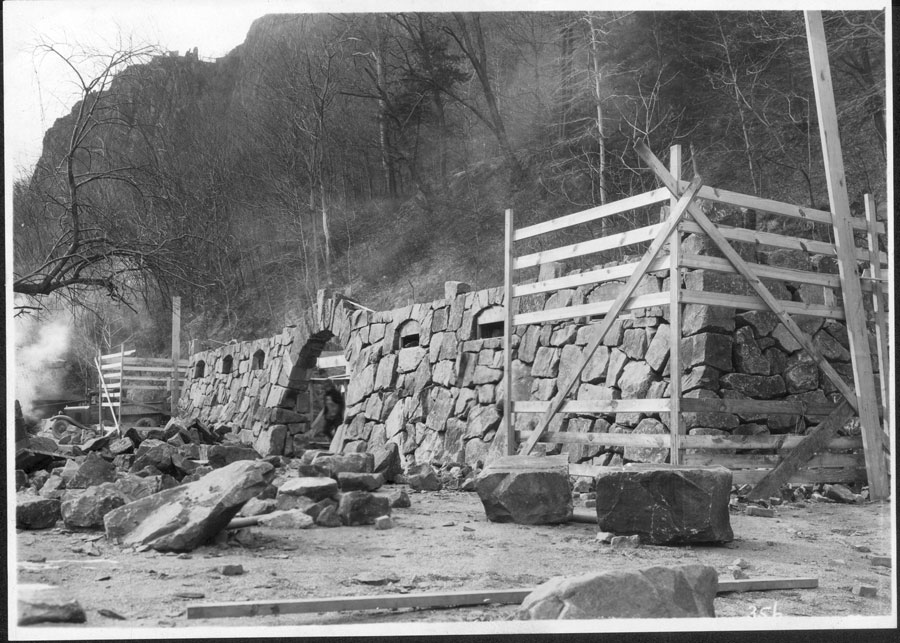

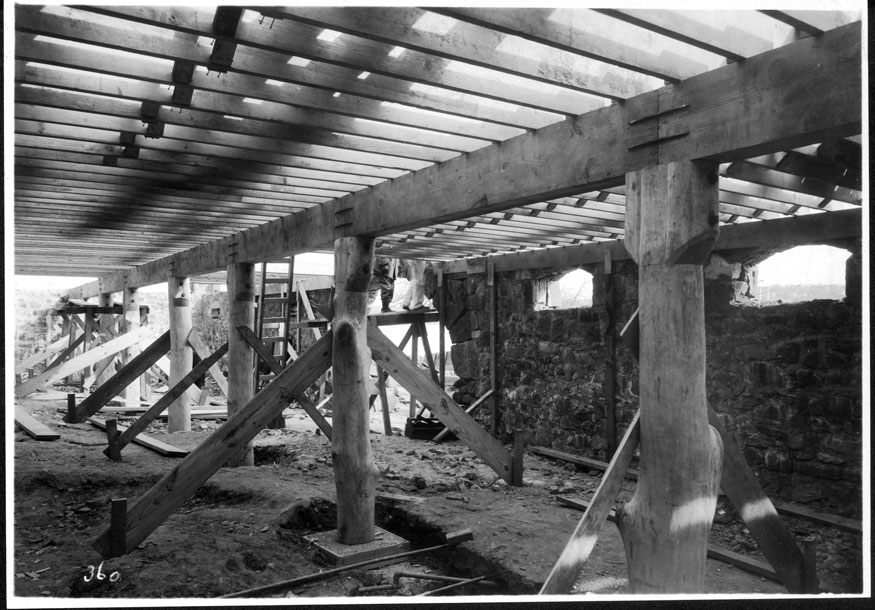

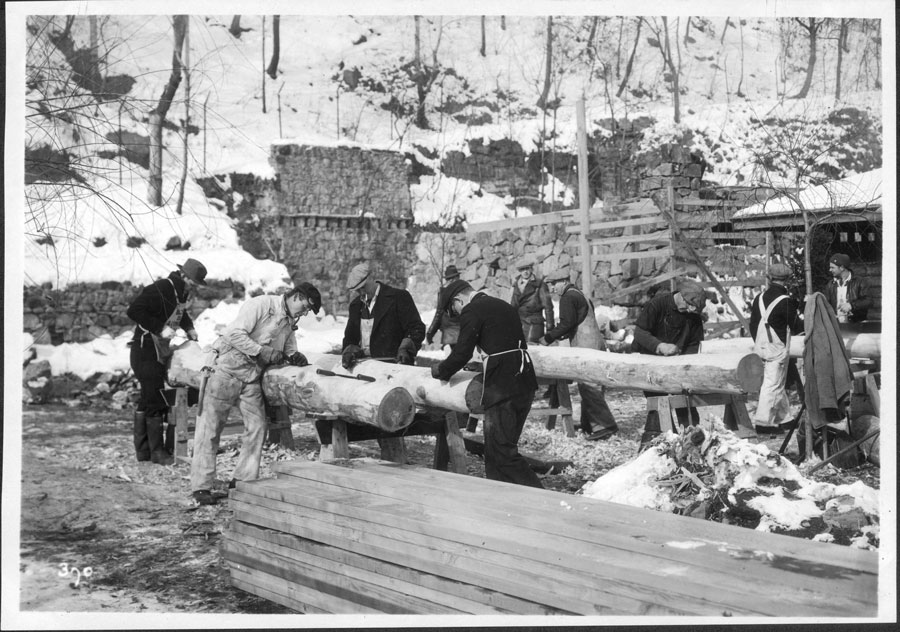

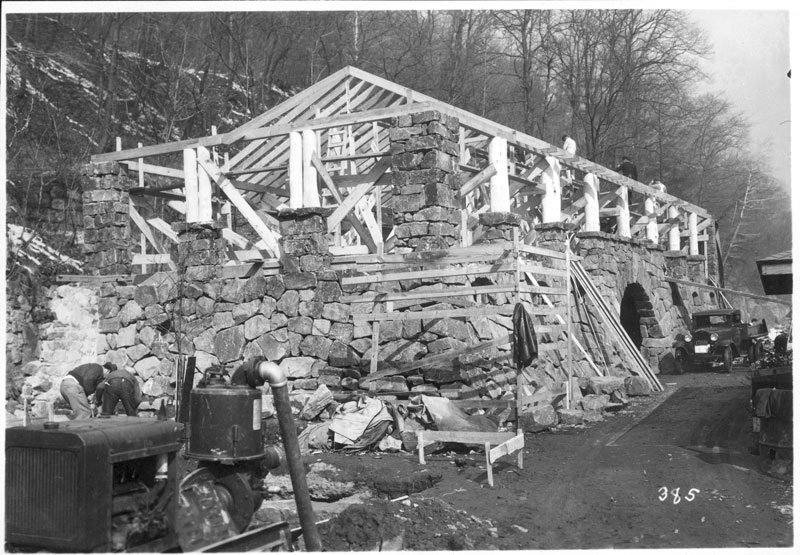

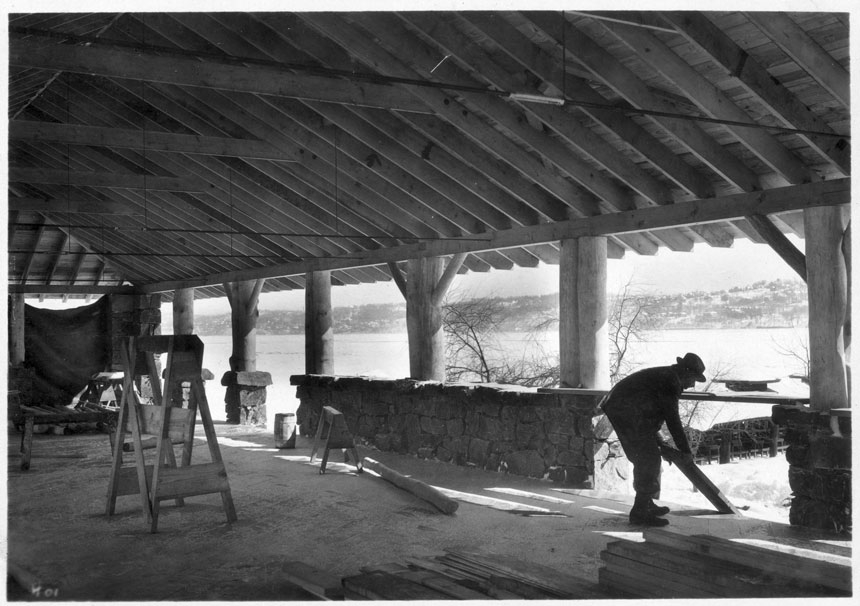

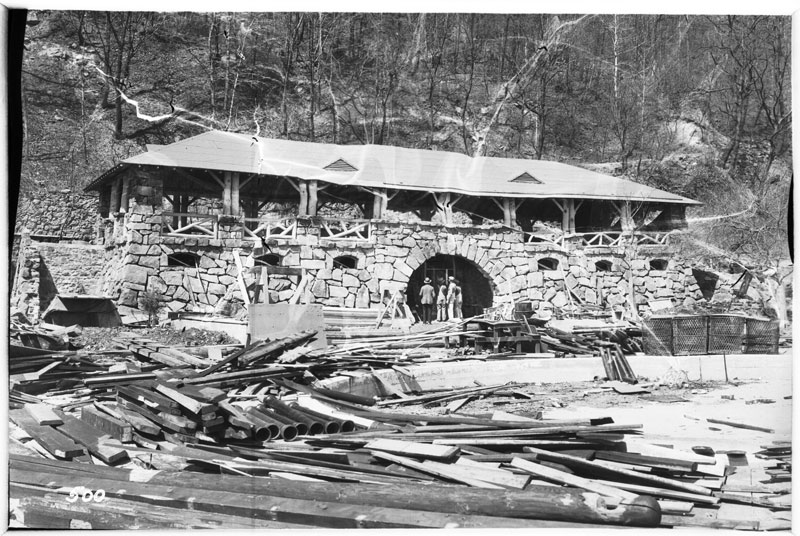

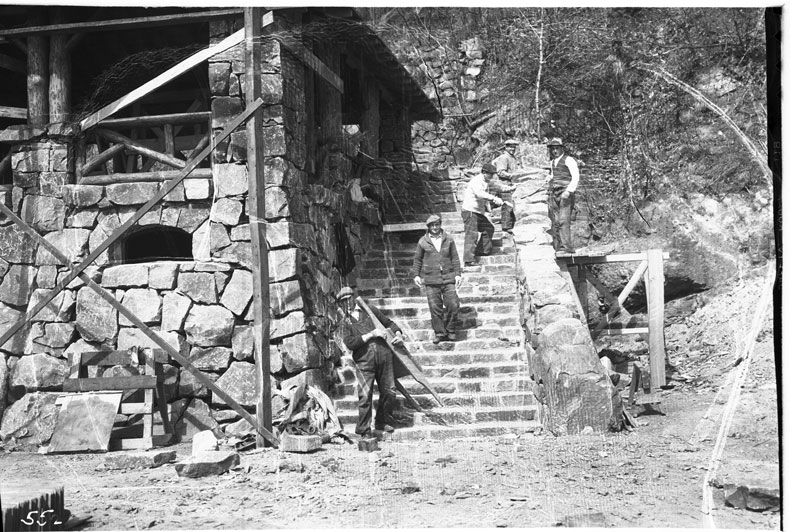

At Alpine Beach, workers hammered together wooden scaffolding and forms, and they built ramps on which to move big stones into place. The walls for the first floor of the bathhouse began to take shape, with a graceful archway for the front entrance. By the end of the month, the crew there had begun to lay wooden beams on top of the stone walls they had just built, for the floor of a second- story open-air picnic pavilion.

The Bloomer’s bathhouse was to have just a single story, sited on a terrace above the beach. Begun about a week after Alpine, its walls and entrance arch were taking shape by the end of the month as well.

Then came February.

The month started with a blizzard, another foot of snow. Then the temperature fell — and fell some more. The overnight low on February 9, 1934, recorded just before sunrise, remains the coldest temperature ever recorded at Central Park: –15 degrees Fahrenheit. In Ridgewood, where some of the workers lived, it was –17. It would not rise above 6 that day. A second February blizzard hit on the 19th; a third on the 25th. By the end of the month, the mean high temperature at Central Park for February 1934 was just under 20º.

It became known as “the hard winter.”

At least once or twice a week a photographer still went through the park and snapped pictures of the progress:

By the time the CWA allotments expired on March 31, over four-hundred-thousand man-hours had been logged in the park. Funding for the projects was picked up at a reduced level by the New Jersey State Emergency Relief Administration.

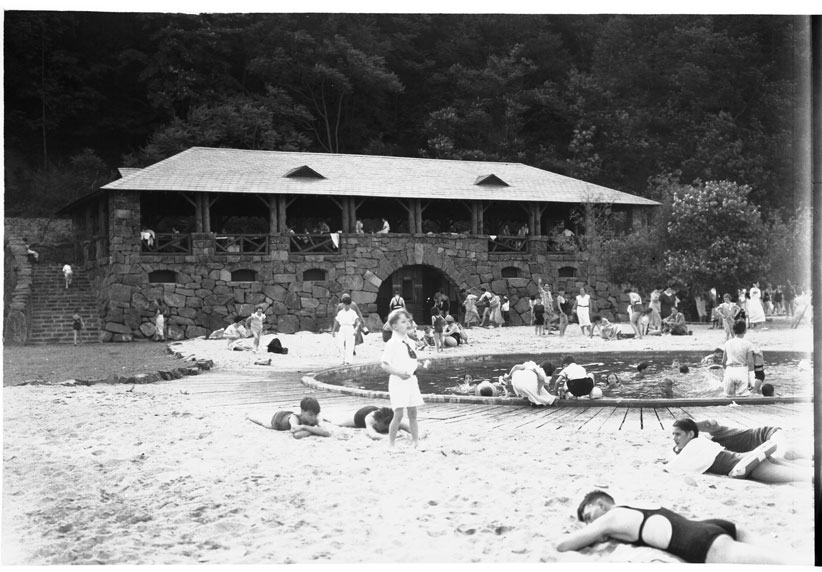

The park’s bathing beaches — with a pair of new bathhouses and half a dozen new refreshment stands — opened on schedule that Memorial Day weekend. They were used by close to half a million park visitors that summer.

The beaches closed a decade later, during the Second World War.

The Bloomer’s bathhouse, “a handsome structure of native stone, built upon a terrace, approached by two semi-circular stairways,” fell into disuse. Today, the walls still stand, but the roof has been removed.

The Alpine bathhouse, now called Alpine Pavilion, “rustic in design and veneered with great boulders” — with “architectural features of unusual beauty and utility” — still stands, even if the beach it was built to service is closed. On most weekends in the warm weather it is the site of parties and picnics, family get-togethers, barn dances, even the occasional wedding. It is also a monument of sorts — to the men who wrested it from the hard winter.

Construction of Alpine Bathhouse during the “hard winter” of 1934

Photos: PIPC archives.

– Eric Nelsen –