Hidden on the Mountain

A “Cliff Notes” Story

June 2021

The State Line Lookout area is far and away the most popular destination for hikers in the park. But often ignored by the hundreds who come here on a nice weekend day is the network of designated cross-country ski trails, five miles of winding pathways spread through the woods to the west of the Lookout — away from the views and the waterfalls and the rock scrambles that attract so many to the area. The ski trails meander through the broad plateau above the Palisades, dipping into marshy forest or rising along the spines of rock outcrops dappled in shade. Here and there the trails also crisscross with walls of fieldstone that slump through the woods, their straight courses bent by trees that have grown in alongside them. A story is being told, if we stop to listen: At one time these rocks were deliberately placed to clear small farm fields, as families eked out a living from the thin soil of the Palisades. It is a story predating the park, hidden on the mountain and among the trails.

Census records from 1840 on show free Black families living here beside their white neighbors, an economically independent, multiracial community throughout the 1800s. Some of the people who lived here had started their lives enslaved, but there was no generational “debt” owed to former masters, in the way later Southern sharecroppers would struggle (though monetary compensation in exchange for manumission was often required). The new community of “Skunk Hollow” grew in size by the 1860s, and over sixty families eventually called it home before its disintegration. But who were they, and where did they go?

Maps, property deeds, and census information can shed light on this unique community of Black men and women, some born into freedom, others born enslaved. In all cases, the story seems to begin with one man, known to us as Jack Earnest.

Our main source of information about this man is the diary of Nicholas Gesner, a white descendant of Dutch settlers who built farms in the valleys south of Tappan. Gesner was born and came of age on a farm in what would become Rockleigh, New Jersey, just west of the park. His diary has plenty of local gossip of the early nineteenth century — as well as a single long entry with much of what we know of Jack Earnest’s story. A seventy-six year old Gesner wrote that entry on Thursday, November 18, 1841:

[He] Was born in My fathers house, a Slave, I Bought him of … My father John Gisner when he was about 23 years-old for £80 is 200 dollars, As I ever was opposed to Slavery, I told him after he had Served me 7 or 8 years I would set him free; this was my true and Real intention…

Gesner’s diary entry recounts how a year after he bought Jack, Gesner’s brother-in-law, Jacob Conklin, would try to lure Jack away, offering not just manumission in seven or eight years — but also his own farmland. Some bad blood existed between the brothers-in-law, and Gesner writes that he advised Jack not to trust Conklin. When Gesner refused to sell the enslaved Jack, Conklin engaged in what Gesner descibes as a “plot” against him. In the end, Conklin would succeed in becoming Jack’s master, and Gesner reports that it took Jack almost double the agreed seven or eight years to gain his freedom — and then “on Condition Jack would secure him One hundred Dollars!!!”

Jack was by then in his mid-thirties. A slave, he had no money — and no last name. A white neighbor, Peter Willsey, was able to secure the hundred-dollar fee for Jack, allowing him to work it off “cutting cord …etc.”

Gesner asserts that he had always had Jack’s best interests at heart, though obviously, in this diary entry written decades after the event, Gesner may simply be showing himself in the best light he can. As it was, he was born on the same farm as Jack but with privilege and security. One held power, land, and the accumulated wealth and prestige of his Dutch ancestors; the other was nameless, enduring, and above all else earnest for manumission.

Jacob Conklin would never give Jack the land he had promised him, either. It would be up to Jack to get his own land — and his own name:

After he left Concklin to do for himself a Nice little property by hard Industry, he was small light Made dark coloured Man, he Was the Son of a Coloured Man belonging to Domina [i.e., Reverend] Verbrycke, who preached at Tappan, and of Yanache a Coloured Woman of my father John Gesner — Jack Earnest was the Youngest of 4, Namely the Oldest Dinah — next Flora next Sam — and lastly Jack — NB the Surname Earnest was Attached to him Because he was in great Earnest when purchasing some land in the Mountain When about to get his Deed — Jacks 2 Sisters and Brother each died With the Consumption When Young, Dina and flore were About 19 or 20 When they Died and Sam About 26 years old, the 2 females died at My fathers, Sam at New York &c…

Deed records show that it was on January 7, 1806, that “Jack Earnest of Bergen County” purchased “five acres and thirty square rods” in Harrington Township for $87.50. The plot was about 300 by 700 feet. He purchased the land from Peter Willsey (the same man who lent Jack money earlier), who agreed to let Jack and his wife, Susan, take a hundred-dollar mortgage on the property. Jack Earnest would acquire a few more acres in subsequent years. He was the first of many who settled atop the “Closter Mountain.”

Among them was James Oliver, who had been enslaved by Johannis Blauvelt; upon Blauvelt’s death, his will set Oliver free. Oliver bought property beside Jack Earnest’s. In time other free Black families would come to live nearby as tenants. By mid-century, there would be over sixty households in the community, which by then had become known as Skunk Hollow. Family names such as the Siscos, Cartwrights, and Olivers would be common in this area for generations.

Land here was attainable for these families due to its relatively cheap price. Skunk Hollow has numerous small, boggy sections, and conditions are not ideal for larger farming operations. (The origin of the name is uncertain — some suggest it may derive from the skunk cabbage that grows abundantly in the area.) The small farms could grow some crops for their own needs, but most of the men worked as laborers on farms elsewhere in the Northern Valley for a wage. There is also evidence that the people of Skunk Hollow manufactured leather shoes for a time. (Today we associate goods like these with a production line in a factory, but in the 19th Century, much of this work could be taken home and sent back to a supplier when assembled.)

In the spring of 1841, Jack Earnest, in his seventies and a widower, sold several acres to William Thompson, a Black man in his late twenties. Six months later, on his deathbed, Jack transferred the remainder of his property to Thompson. Jack Earnest had been involved in a tragic accident — the very reason Gesner recorded his diary entry about him that day in November, a fresh snowfall — the first of the season that year — covering the ground outside his window:

Last Night Jack Earnest at Home laid himself before the fire probably in his sleep, his clothes took fire, got out doors, and before he could get his clothes off, Was Mortally burnt, it is said one ear was Roasted — being alone, in the house, and awfully burnt, he put on his great coat and Went in the Night to the house where John Cartright lived (a Colored Man) a quarter of a Mile distance … This afternoon he died; what an awful death! … Was About 71 Years Old …

In 1856, William Thompson and his wife, Elizabeth, deeded a fifty-by-fifty-foot plot to the trustees of the “Methodist Episcopal Church of Colored People of the Township of Harrington.” Later census records show Thompson as a Methodist Preacher in Skunk Hollow, where there was a strong congregation. Although their founder was gone, the community continued on and it was in good hands.

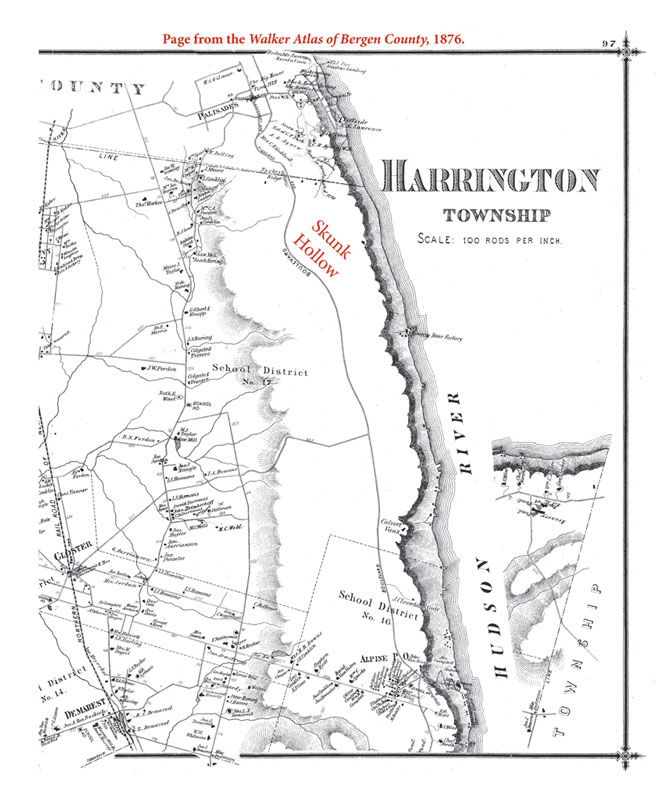

Page from the 1876 Walker Atlas of Bergen County annotated to show the location of Skunk Hollow — a settlement of dozens of families left as blank space in the atlas, published to coincide with the Centennial celebrations of the United States.

In a future story here, we will share our research into the later history of this community.

Revised and edited from a story originally published in January 2013.

– Francesca Costa & Eric Nelsen –