The March of the Forgotten

A “Cliff Notes” Story by John Spring

September 2001

You can also view a video adaptation of this story (created in April 2023)!

Much has been written about the supposed landing of a British army at the Old Closter Dock on November 20, 1776. This, in spite of the fact that most documentary evidence shows that the invasion was made over a mile south of that point at the New Closter Dock (later Huyler’s Landing).

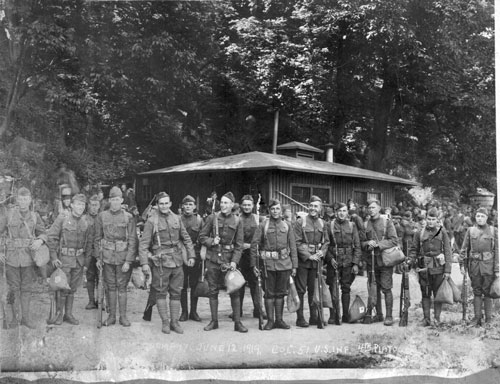

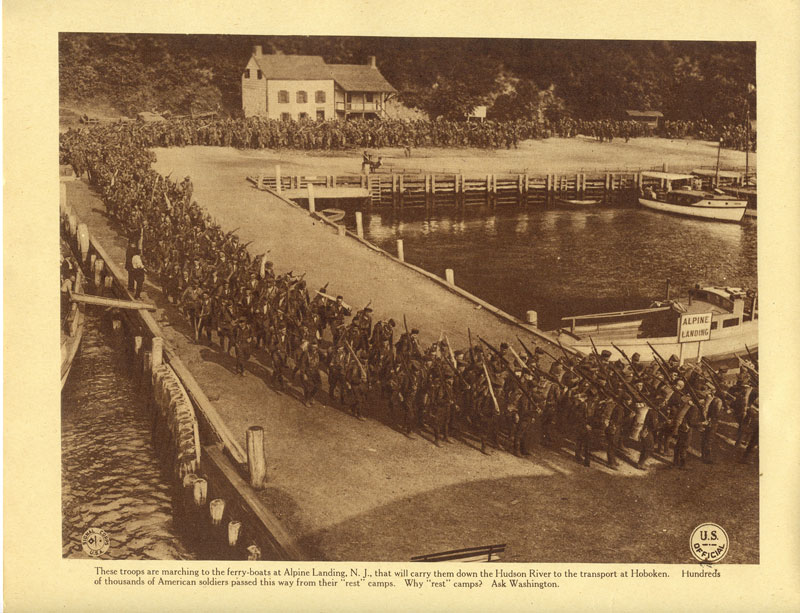

However, there is no doubt whatsoever that a much larger number of men — and perhaps some women nurses — passed through Old Closter Dock in 1918, during World War I.

These troops were the ones coming from Camp Merritt, the huge embarkation camp built in 1917 at the Cresskill-Dumont border and touching the towns of Demarest, Haworth, Bergenfield, and Tenafly. It encompassed 770 acres and was strictly for the embarkation of troops from the port of Hoboken — the soldiers having been trained at other, older camps throughout the country.

Towns throughout the Northern Valley went all out to make the soldiers’ last days before embarking as comfortable and enjoyable as possible. The camp’s facilities were the newest and best in the entire country and residents bent over backwards to accommodate families who poured into the area to visit their sons before their departure for France.

One spry Cresskill resident, Mrs. Gladys (Muffy) Pendergast, recalls today how she and her siblings doubled up in her Hillside Avenue home so her parents could take in visitors seeing off their sons. She also tells of using a garden hose to fill a water bucket with a dipper to drink from for troops who were marching from the camp to the ferry.

Mrs. Estelle Tallman, in a house just west of the Cresskill station, told of using lawn chairs on her porch for visitors to rest in when all her rooms were full.

Not all of the soldiers who marched from the camp to the ferry went willingly. Some were what Howard Rose’s book Camp Merritt calls “Casual Troops.” These were men who showed up in camp without papers, having been in the hospital or gone A.W.O.L., perhaps deciding to visit home for Christmas while it was still possible. Officers had their hands full trying to decide how to handle such men. They finally decided to form them into companies and ship them overseas. There, if the soldiers went A.W.O.L., they could be charged with desertion.

Letters from one soldier who guarded the stockade where casuals were held tell of conducting a group of them to the ferry at night, when one of them broke away as they were marching down the road to the ferry. A guard shot at him, but it was later the next day before they found his body in the woods along the Palisades.

Not all troops leaving camp for Europe went to Hoboken by ferry. Many went on the West Shore railroad from Dumont, or on the Erie trains through Tenafly and Englewood. That route was also used for a more macabre cargo at times. Tony Urato of Bergenfield relates that his wife told him of trains going slowly through Tenafly stacked with coffins carrying the bodies of soldiers — and perhaps some nurses — who had died of influenza at Camp Merritt.

The influenza of 1918, after passing through various army camps here and abroad, assumed an entirely different form than the usual three or four days of coughing, headaches, and fever that was its pre-war pattern. That form of “flu” had not even been a reportable disease for doctors before the war.

But in 1918, soldiers from European battlefields went for R and R to a rest camp in Spain, where almost all of them caught the “flu.” It was a mild form, but almost 100 percent of the men were infected. Thus, the epidemic acquired the name of “Spanish” influenza. Many of these men acquired immunity to later, more deadly forms of this flu.

Then, as summer turned to Autumn in 1918, doctors faced a form of influenza they had never seen before. Men and women in their prime would sicken and die in a day, their lungs saturated and heavy. By the middle of September, the best doctors knew only that, in each camp or locality, the epidemic would reach its peak in about three weeks, then subside. They begged the military to delay troop shipments till that peak passed. The officers, under constant pressure to get troops to the front, ignored them.

On the night of September 27, 1918, troops from Camp Merritt began to march to Alpine Ferry. But, as they marched, some began to fall by the wayside — with the flu. Ambulances and trucks took some of them back to the camp. Volunteers helped others get back. Other infected soldiers boarded the ferry for Hoboken, where doctors tried to weed them out before they boarded the Leviathan — the world’s biggest ship, a converted liner — for shipment overseas.

Leviathan had had extra capacity added so it could take more men. A contingent of nurses was aboard as well, but the nurses could not climb to the top of the four-tiered bunks—and the sick men could not climb down. Men lost their dog-tags and were buried at sea, in spite of a policy that all soldiers were to be returned to the States for burial. The loss of life on the voyage could only be estimated.

Shortly after this voyage, doctors placed Camp Merritt under a quarantine which lasted until the November armistice ended the war. Perhaps because it was such an unpleasant memory — contrasted with dying gloriously in battle — the episode was quickly forgotten.