“A Monopoly of the Bad Business”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

July 2023

July is the hottest month of our calendar year. Tempers run high and blood boils quickly. While the largest civil upset in this country’s history was the Civil War, the second largest would take place in July of 1863 — amidst that very war — in the crowded streets of New York City. And several Palisades residents would witness it firsthand!

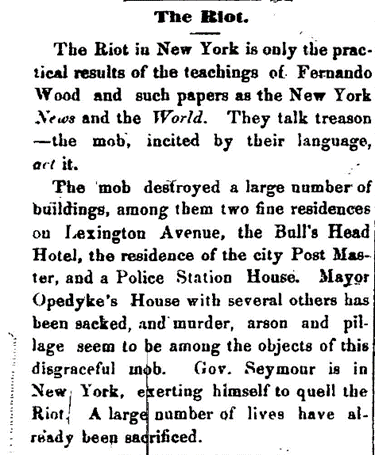

On July 13th, hundreds of New Yorkers directed their simmering ire against the newly-instituted draft for the United States Army toward a provost office that was helping to conduct that draft. Reasons for their gathering ranged from class disparity to frustrations about the war. Many in the mob openly sympathized with the Confederacy. Just two weeks earlier, 27,000 New Yorkers had participated in the Battle of Gettysburg. A thousand of those native sons died on that battlefield, joining thousands of other New Yorkers who had been killed or maimed in the now two-year-old war. While many historians believe Gettysburg definitively changed the tide of the war, New York City — then consisting only of Manhattan Island — was about to enter a period of extreme uncertainty. With most military units off fighting the war, the island was largely defenseless. On that summer day in 1863, Confederate-sympathizing men began to murder public officials and set buildings on fire. This soon swelled into a larger civil disturbance, with more intention behind the attacks: telegraph lines were cut to delay communications, cart horses killed to block the streets from police resistance. The violence would only grow over the oncoming days of terror.

The Miller

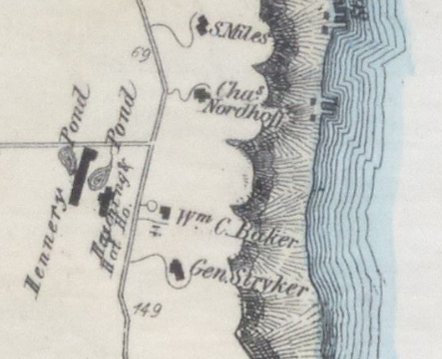

Francis Miles was an industrialist living atop the Palisades in an area we now call “Millionaire's Row.” (His younger brother, Colonel Sweeting Miles, would soon join him along the Palisades, but in 1863 operated a mill in Jordan, New York, along the Erie Canal, where he helped form the 74th NY Infantry.) The Miles brothers knew how dangerous New York City was and had experienced the ineffectuality of local fire brigades. Two years earlier, in November 1861, The New-York Sun had reported:

The split pea and barley factory of Francis S. Miles, No. 48 Harrison street, took fire at 12 o’clock on Saturday night… Engine companies Nos. 11 and 47 had a race on the way to the fire, and two of the members of No. 11 were run over, and also one of the No. 47. Engine Company No. 42 and a Hook and Ladder Company had a fight on the corner of Chambers street and Broadway. Pistols were fired, and brickbats, wrenches, trumpets and other missiles were freely used. One of the members of the Hook and Ladder Co. was badly hurt.

Fire was a major and constant danger in a city built from wood and brick. Between organized crime, turf wars between fire brigades, and political tensions reaching fever pitch, Francis Miles was in a precarious position when the Draft Riots began. His business and offices were right next to the docks, where most of the active instigators made their livelihood. We cannot know exactly where Francis Miles was during the riots, but his business was in a powder keg.

Fires would burn large swaths of the city that week, and firemen who were drafted refused to quench the flames. Francis Miles was able to survive this riot, though the future of his landholdings in the city would be left to the mercy of a mob.

The Lawyer

William Stryker Opdyke was another long-time Palisades resident and was a staunch Republican during the Civil War. He organized town hall events titled, “Questions about the War,” to have a public dialogue about the necessity of the ongoing conflict. In 1861, he passed the New York Bar exam, and by 1863, he became a member of New York University's administration. Later, he would become a State Representative, and enjoy a summer estate along the Palisades. His family would remain close to the Miles family and others along “Millionaire's Row” for generations to come.

During the Draft Riots, Mr. Opdyke found himself a high-profile target. Throughout the first day of civil degeneration, the mob moved south from 47th Street. His family’s textile factory on Second Avenue and Twenty-first Street was burned to the ground, while people called for Opdyke blood. Irate men and women sacked his father’s house on 5th Ave, and his mother was only able to escape through the assistance of neighbors.

But why was the Opdyke name being called for in the street? And so fiercely? William’s father, George Opdyke, was the first Republican mayor of New-York City, serving from 1861-1863. He barely won his election with a measly third of the votes, and his Tammany Hall opponents were vicious. The previous mayor, Democrat Fernando Wood, urged that New York City secede from the union and become an independent city-state in order to continue its prosperous cotton trade with the South. Many agreed with Wood, identifying more as a city than as a larger union. New York City had become a microcosm of the Civil War in all its violence.

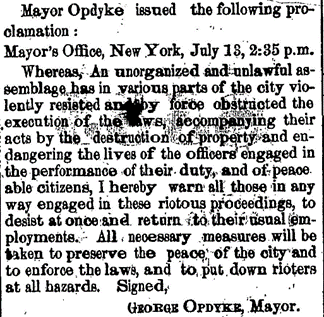

Mayor Opdyke’s political career was shrouded in controversy for a few reasons. Not only did he spend $20,000 on Lincoln’s election campaign, but he was a loud proponent against slavery. Critics called him a hypocrite, as he had made his vast fortune in Louisiana selling cheap clothing to plantations. As crowds descended around City Hall on the first day of riots, Mayor Opdyke released a statement. He rejected the demands of Tammany Hall politicians, but did not declare martial law. Instead, he was forced to flee City Hall and hide at a local hotel, saying “Rioters must be conquered, not conciliated.”

A city of one million people was dead silent, save for where people were actively rioting. And so, as night passed, people held their breath. The Rockland County Messenger later wrote (on July 23), “Better New-York be laid to ashes than submit to the dictation of a mob.”

The Journalist

Charles Nordhoff loved his Palisades estate so much that he built a large watchtower upon it, overlooking Yonkers and the Bronx. Nordhoff was long-time friends of the Miles Brothers and the Opdykes. He made his fortune writing adventure novels based on his time spent in the United States Navy and then on merchant vessels, before settling down to become one of the highest-paid political journalists during the Civil War. He was on a first-name basis with the Washington politicians orchestrating the war effort and wrote supportively about the Union’s efforts. Unfortunately, Nordhoff found himself within New York City during the Draft Riots. Not only did he provide a narration for these events, but he committed the journalistic sin of “becoming the news.”.

On the second day, Charles Nordhoff accompanied an undercover Police Superintendent of New York to see the angry crowd. The mood soured as people in the crowd recognized the policeman amongst them. After they gave the Superintendent a sound thrashing and 70 stab wounds, Nordhoff heard a shout. This time, someone had recognized him, and they were shouting, “Here’s a damned Abolitionist! Hang him!”

After the beating, when Nordhoff regained consciousness, he realized he had been left for dead. Stubbornly alive, he limped back to his newspaper building to write. Though other newspaper buildings were targets during the Draft Riots, Nordhoff’s Evening Post was not assailed.

His biographer explains:

The upper floors of the Evening Post building had been converted to a hospital for wounded Union soldiers and presented an obvious target to the rioters. Nordhoff, shaken and furious after the ugly scenes he had witnessed, saw assault on the Evening Post as an attack on free speech and democracy itself and posted notices warning that he had attached hoses to the building’s steam pipes and placed them so that any marauders could be sprayed with boiling water (a less lethal defense than that of the New York Times [who used gatling guns], at least). It was later remembered that he stayed at the Post building for days on end during the riots, ‘quietly smoking and writing while the mob howled outside.’ The Post did not interrupt publication that week. …

The only time Nordhoff left the city was to give his wife incendiary devices which she could use to defend herself and their Brooklyn home, if riots were to break out there. But prominent Republicans were only one group the mob of Irish longshoremen and dockworkers turned on. By the end of Monday, the Colored Orphan Asylum and countless city blocks were on fire, targets of racism and hatred. Their Black residents faced a difficult decision: flee the island or face the lawlessness of Manhattan Island.

The Boatmen

The multiracial residents of Huyler’s Landing on the Palisades timed their lives to the pull of the tides. Black freedmen like a young Thomas Brown would sail downriver to Fulton Street’s market carrying Jersey produce on the tides. On the return trip, his crew would bring all manner of goods upriver. These communities interacted with dockworkers and would be familiar with the City and her unsavory sides.

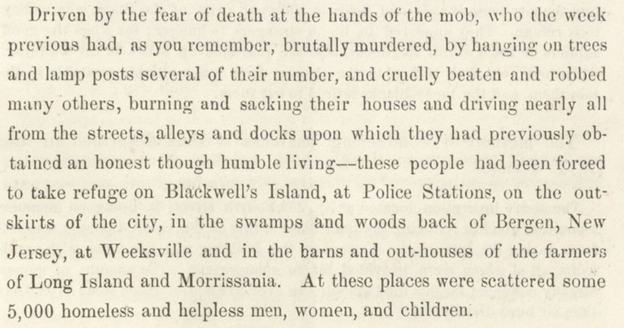

New York City was home to around one million people during the Civil War. Though the draft was a major concern, Irish dockworkers and longshoremen made up a large percentage of the rioting demographic. Black people enraged these immigrant groups more than other competing populations along the piers. Countless Black families along the Hudson and East Rivers lost their homes, livelihoods, and lives. It was not about the draft as much as it was about ousting competition and spreading terror. And the results were clear— 20 percent of the Black population of New York City left in the years after the Draft Riots, leaving their (predominantly) Irish attackers with improved job security.

As the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted:

Colored women and children have been for days past, fleeing from this Christian city as though it was inhabited by wolves. We do not appeal to the authorities mainly; we appeal to the manhood of the people… Let New York have a monopoly of the bad business of tyranizing over the weak. Let us, for the honor of our city [Brooklyn], of our blood, of our race, of our manhood, refuse to imitate her bad example.

During the chaos of 1863, there were also people doing what they could to help counter the mob. Firemen carried wounded Black children from one house to the next, begging for someone to hide them. Armed veterans, recently back from the carnage of the war, began organizing and roving the island to fight armed and murderous dockworkers.

If any Palisades boatmen were near New-York City, they might have participated in the following aqueous evacuation. Ferries, skiffs, fishing boats, and sloops carried thousands of Black New Yorkers away from their docks and imminent threat of murder. Within three days of rioting, more than 5,000 refugees were secreted away to the nearby cities of Brooklyn, Hoboken, and Jersey City. Others fled to the Salt Marshes of the Meadowlands in New Jersey, where they were without water and food for days. One out of every 200 New-Yorkers left the city during these riots. Some never returned to the horrors they left behind. Newspapers decried the devastation, and in the aftermath, charities began to assist those who lost everything. Wall Street businessmen began recording these stories and compiling funds to support bereaved families.

And so, some of the ugliest days in New York City’s history came to an end. U.S. Troops fresh from the battlefields of Gettysburg were marched through a Northern City to restore order. They saw how a Civil War impacted the population so far from the Mason-Dixon Line and how complicated this fight was. The Palisades would be a welcome refuge for Charles Nordhoff and William Opdyke. “Commuters” such as Francis Miles and Thomas Brown spent their lives beside the cliffs but still depended on the city in all her chaos for their livelihoods.

– Francesca Costa –