A Most Alluring Pest

A “Cliff Notes” Story

March 2025

Easily recognizable with black spotted wings that flash crimson during flight and relatively hard to miss, the invasive spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) originates from eastern Asia, and within the past decade has taken up residence in the United States. In 2014, the first lanternfly infestation in the country was reported in Berks County, Pennsylvania. The suspected culprit? A Chinese shipment of stone which arrived two years prior, believed to have had lanternflies on board.

It may be surprising to learn that lanternflies are not flies at all. These bugs are “planthoppers,” a broad term for a diverse group of insects named aptly for their ability to hop far distances. They boast straw-like mouthparts that are able to pierce plant tissue, giving them access to the sweet juice and sap inside. Lanternflies do not bite or sting and are technically harmless to humans and animals … but “harmless” is a relative term!

More than an eyecatching nuisance, the spotted lanternfly has wreaked ecological, agricultural, and commercial havoc throughout the Northeast. Lanternflies are swarm feeders, meaning they gather in dense packs to feed on one food source. When planthoppers feed, they excrete a waste product known as “honeydew” to expel excess sugar from sap consumption. Because of its high sugar content, honeydew often attracts other pests that are detrimental to plant health, and accumulated honeydew becomes the perfect medium for layers of sooty mold fungi to grow. This fungus impacts plant health, impeding photosynthesis and leaving vegetation vulnerable to disease.

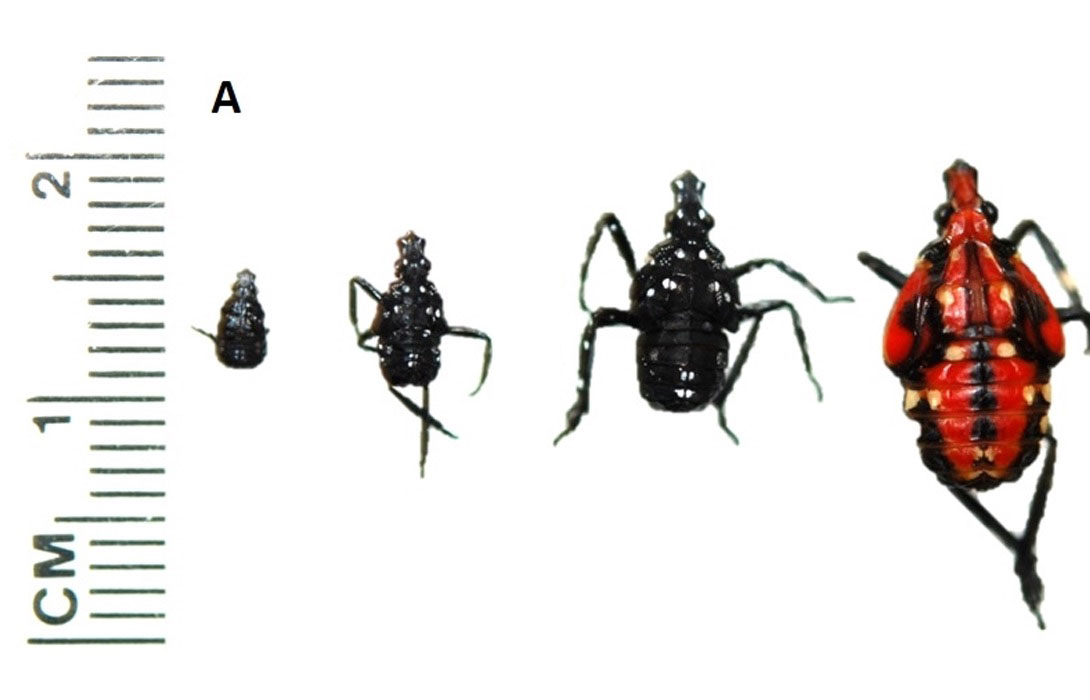

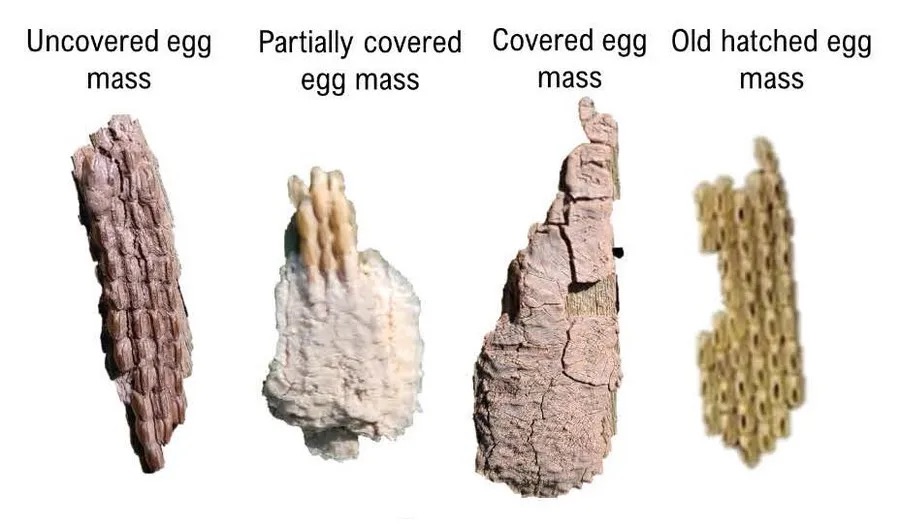

Spotted lanternflies undergo one life-cycle per year, including four developmental nymph (juvenile) stages and one adult stage. Eggs begin to hatch in May, and the young planthoppers emerge as black nymphs approximately ¼” long with white spots. They spend the first three nymphal stages with this coloring until approximately July to mid-August, when they molt into the final nymphal stage and develop a red coloration. Adult lanternflies, approximately 1” long, can be seen from July through December. Adults possess spotted, pinkish-brown wings with similarly dotted bright red underwings, a yellow striped abdomen, and a 2” wingspan. Female lanternflies begin laying their eggs in September up until the first major frost, when late-stage adults begin to die off. Females can lay up to 60 eggs at once in 1” rows. They will cover the rows with a white, mud-like substance that dries pinkish-brown; after several weeks, the covering develops a darker coloring and begins to crack. Egg masses can be observed on any hard, flat outdoor surface, including tree bark, firewood, outdoor furniture, rocks, and vehicles.

Throughout its nymph stages and into adulthood, the lanternfly has been documented feeding from more than 70 species of flora. Once it reaches the fourth nymphal stage, its preferred host plant becomes the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), a deciduous tree native to China and an invasive species in the United States. Unfortunately, even removal of Tree of Heaven has its complications, as an aggressive system of roots means that cutting down these trees only exacerbates new growth. As adult lanternflies mature, they begin to stray from the Tree of Heaven and develop a preference for grape vines, silver maple trees, black walnuts, willows, and other hardwoods.

For agriculturists, the lanternfly has proven to be especially damaging to cultivated grapevines. Heavy feeding (some farmers have reported up to 400 spotted lanternflies on one vine) can lead to a decline in grape yield, reduced winter hardiness, and even vine death. The sooty mold that grows from honeydew can also damage crops, making them unsellable. Beyond its impact on agriculture and natural plantlife, hoards of lanternflies and the sticky residue they leave behind can have a considerable impact on public enjoyment of natural areas - even one’s own backyard. Fears regarding breaching county lanternfly quarantines have also created exporting difficulties and have increased the cost of management in an attempt to alleviate such issues.

ortunately, lanternflies may not be as damaging to hardwood trees as previously thought. In an effort to better understand the long-term impacts of seasonal feeding on hardwoods in the northeastern United States, a research team at Penn State University spent four years rearing lanternfly colonies in enclosures containing different species of trees. They found that although repeated heavy feeding over the course of two years did lead to a reduction in tree nutrients and therefore a reduction in tree growth, lighter feeding the following year allowed all native trees in the study to fully recover.

If you live in the Northeastern United States, you likely have been encouraged to “see it, squish it, report it!” After months of doing so, why are so many counties still under quarantine, and why are these pests still out of control? Unfortunately, lanternflies are master hitchhikers and are easily transported by human activity. To make matters worse, because their eggs can be laid on most outdoor surfaces, any vehicle or item being transported to a new location becomes a mechanism for the spread of new infestations. Lanternfly egg masses camouflage well and are easy to misidentify. Although birds, arachnids, and other insects predate lanternflies in the wild, this does little to mitigate the overabundance of the planthoppers.

So, what can be done? Luckily, many measures on both governmental and community levels are being taken to manage infestations. The New York State Integrated Pest Management Program and similar organizations have released checklists to reference when traveling to or from an area with a known spotted lanternfly infestation; they also include high priority locations to check for egg masses. Experts recommend destroying egg masses if identified by scraping them off with a flat object such as a credit card, and ensuring they do not hatch by crushing or burning them. For nymphs and adults, handheld vacuums have proven useful in collection to circumvent the planthoppers’ quick movements and charged hops. Certain insecticides in the form of trunk injections, bark spray, and root drenches have been recommended for use against the pests. Researchers are also working on rearing certain fungi and parasitoids that target lanternflies at all stages in the life cycle as a form of biocontrol. In a study conducted by Cornell researchers, two fungi native to the United States were found to have killed hundreds of lanternflies!

As of November 2024, active lanternfly infestations are present in seventeen states in the US, highly concentrated on the east coast but extending well into the midwest. Statewide quarantine regulations are active in New Jersey, Connecticut, and Delaware, and multiple counties in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio are also under quarantine. Stopping the spread means a collaboration amongst both federal and state organizations, as well as members of the general public. For now, keep stomping, scraping, and spreading the news!

– Clare Daughtrey –