Skirt Check

A “Cliff Notes” Story

July 2011

They say there was a ferry from Yonkers before the Schwarzsteins. The story goes that David Sims — he was a son-in-law of Rachel Kearney, for whom the Kearney House is named — kept a little fleet of blue rowboats: his boys would row you across for a fee, or you could row yourself. Later, in 1868, “The Yonkers and Alpine Ferry Company” was incorporated by some of the same men who were building big houses on the cliff top and contriving to change the name on the map from “Closter Landing” to the more euphonious “Alpine” (they got their way).

In May 1894 the Times noted that from Yonkers “[a] ferry runs to Alpine, on the west side of the Hudson, whence the top of the Palisades is easily reached. An extensive view is there to be had over Westchester County to Long Island Sound…” In August that same year, the Times reported how the ferry owners were graciously permitting mothers to bring sick children aboard, and to remain in the fresh air as long as they wished.

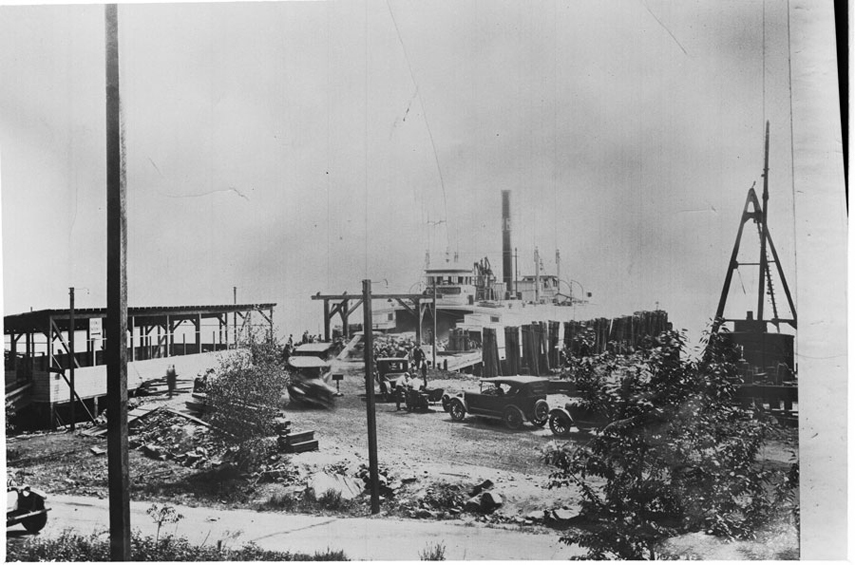

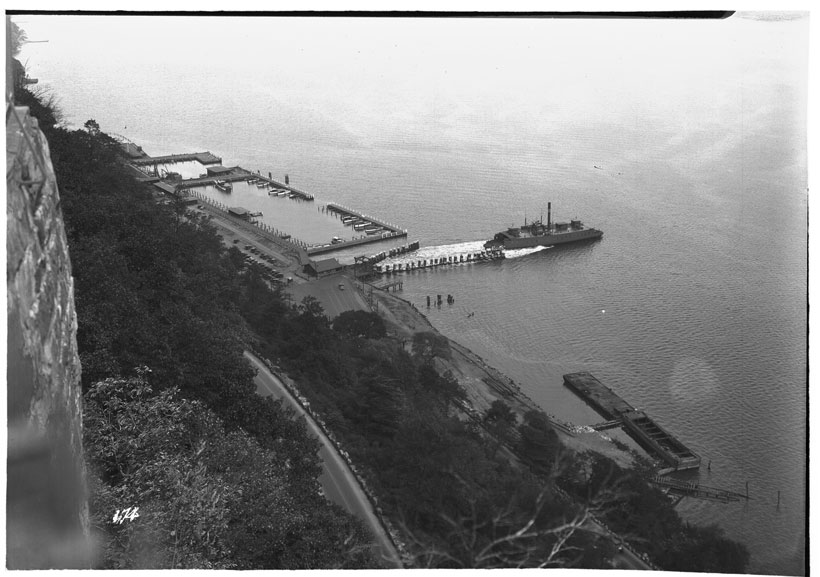

This one and that one took over the operation, failed or got out, sold to someone else — until 1923, when the Schwarzstein brothers, Leo and Jack, formed the Westchester Ferry Company. The Schwarzsteins would see the Yonkers Ferry through the next three decades, right to the bitter end. At the outset, the Park Commission agreed to build Alpine Approach Road from the ferry dock to the highway on top of the cliffs (present-day U.S. Route 9W), to accommodate automobiles. The brothers started out with a pair of side-wheel paddle boats, which they ran from six in the morning until quarter after midnight, every fifteen minutes on weekends and holidays, every thirty minutes on weekdays. The mile-long trip across the river took seven minutes, and the boats could carry twenty-seven cars and several hundred passengers on each crossing. Even after the George Washington Bridge opened seven miles downriver in 1931, the Yonkers Ferry remained a major crossing point for motorists, with over 300,000 vehicles crossing annually. Meanwhile, with trolley connections from the Bronx and northern Manhattan to Yonkers, many of the pedestrian passengers the ferry carried were bound for the Palisades, for a day of bathing, hiking, and picnicking during the warm-weather months. (Except for the occasional mild winter, like ’32, the ferry closed for the winter months, when ice clogged the channel and filled the slips.)

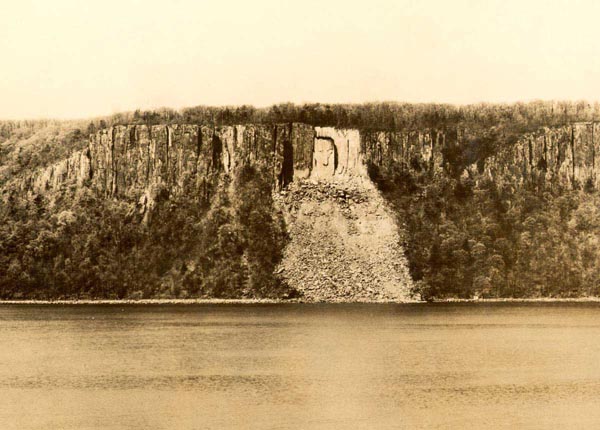

The Schwarzsteins proudly promoted their Yonkers Ferry, inviting musicians and organ-grinders — with monkeys, of course — to play on their boats; they cultivated their contacts with the press, so that stories appeared regularly about ferry captains stopping a boat for ducklings in a slip, or rescuing an overturned canoe, or sending a lifeboat after a Russian wolfhound that had lunged overboard after a seagull. One Schwarzstein family story recalls how one summer ferry crews planted snow stored from the winter in crevices in the Palisades, claiming it to be a remnant of the great glaciers — worth taking a ride across to see. It was the brothers, too, who brought the “Hitler Face” on the Palisades opposite Yonkers to national attention in the early 1940s — the “face” being a trick of light and shadow caused by a rockslide, in which some saw an uncanny resemblance to the dictator (and which, eerily, got erased by a subsequent rockslide in 1945, shortly after the actual Hitler’s demise).

But the brothers’ greatest publicity coup may have been in the summer of 1935, when they offered a “skirt check” service at their Yonkers terminal. It began with a Yonkers City ordinance sponsored by an alderman, William E. Slater of the Ninth Ward, banning, as the Times phrased it, “excessively meager dress within its corporate limits.” His constituents, Slater claimed, were distressed at the sight of young women heading from the trolley to the ferry, bound for the park, wearing shorts. On a Sunday in June, with an eye to voters on their way to and from church, Slater ordered the police to enforce the ordinance, personally signing a complaint against five girls from the Bronx on McLean Avenue en route to the ferry terminal. (The girls were eventually discharged with a warning.)

Within days, the Times reported how “the ferry line operators have undertaken to protect their patrons against the Slater anti-shorts campaign, which is especially vigorous on Sundays. Jack Schwarzstein, terminal manager for the line … announced today [a] new dressing room and check room would be ready for free use next Sunday. Girls may wear skirts over their shorts while passing through the streets here on their way to the ferry, leave the skirts at the ferry-house, hike in the park on the Jersey shore in their briefer outfits and pick up their modesty again on the return trip.”

The Tappan Zee Bridge — the “Thruway Bridge” — opened in 1955. With revenues falling, the Schwarzsteins announced that the ferry would close. New York Governor W. Averell Harriman pushed to keep the crossing open; organizations and residents passed petitions “urging that action be taken to keep the ferry in operation,” asking the Port Authority to take over operations. All for naught. The ferry made its final crossing Christmastime 1956; several years later, its Jersey slip was made into an extension of the boat basin at Alpine Picnic Area.

– Eric Nelsen –