Stranger Than Weird

A “Cliff Notes” Story

March 2001

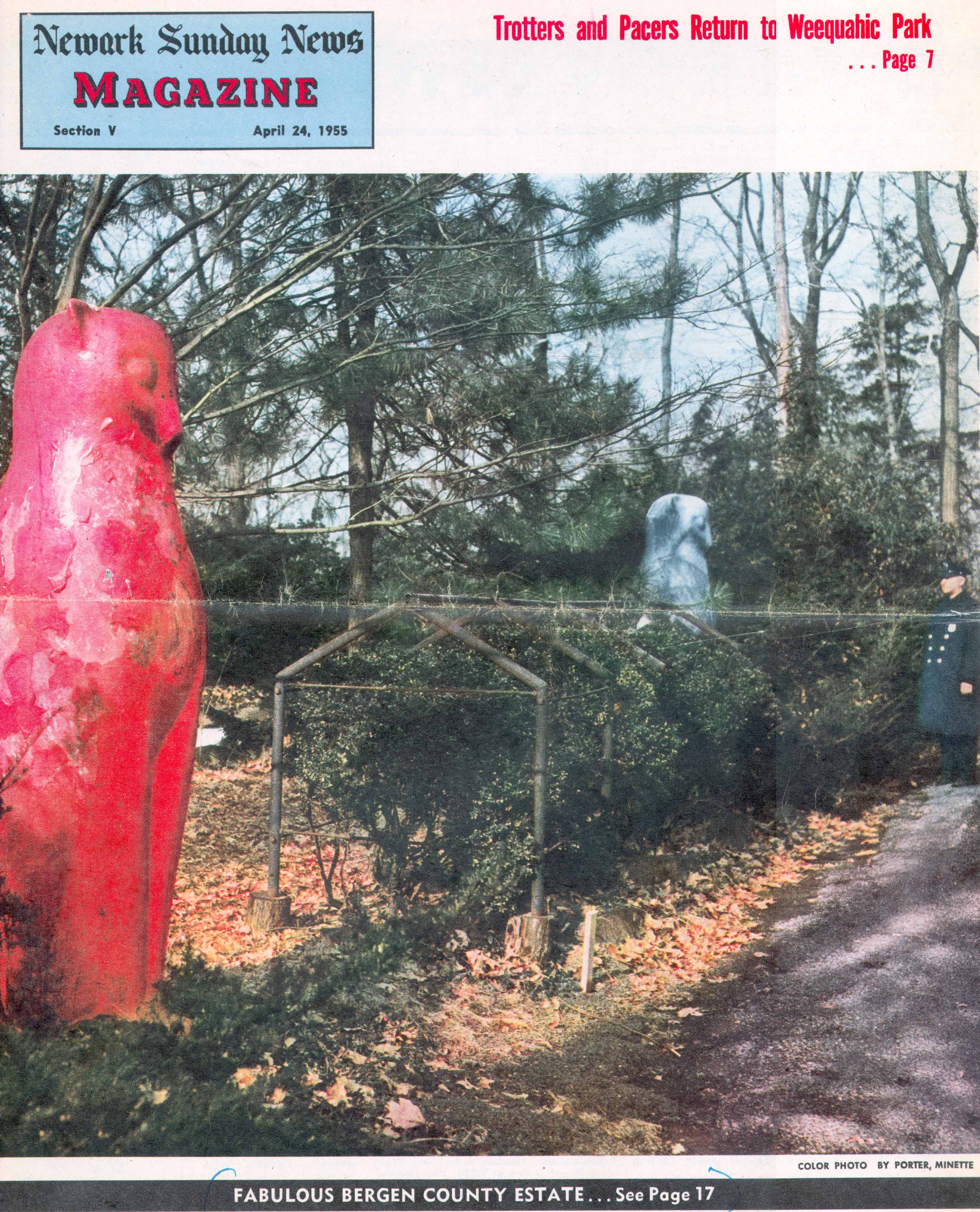

Longtime Palisades hikers often ask us about the mysterious “elephant house” they remember near the Women’s Federation Monument on the cliff top in Alpine.

The magazine Weird NJ even featured an article about this structure, which “lay abandoned in the woods, like the lost elephant graveyard made famous in the old Tarzan movies” — and which about 30 years ago simply vanished, “as if a giant hand had come down and wiped the house off the face of the earth.” The implication would be that no one knows just what the house was, or who may once have lived in it.

Hmm. Had someone given us a call…

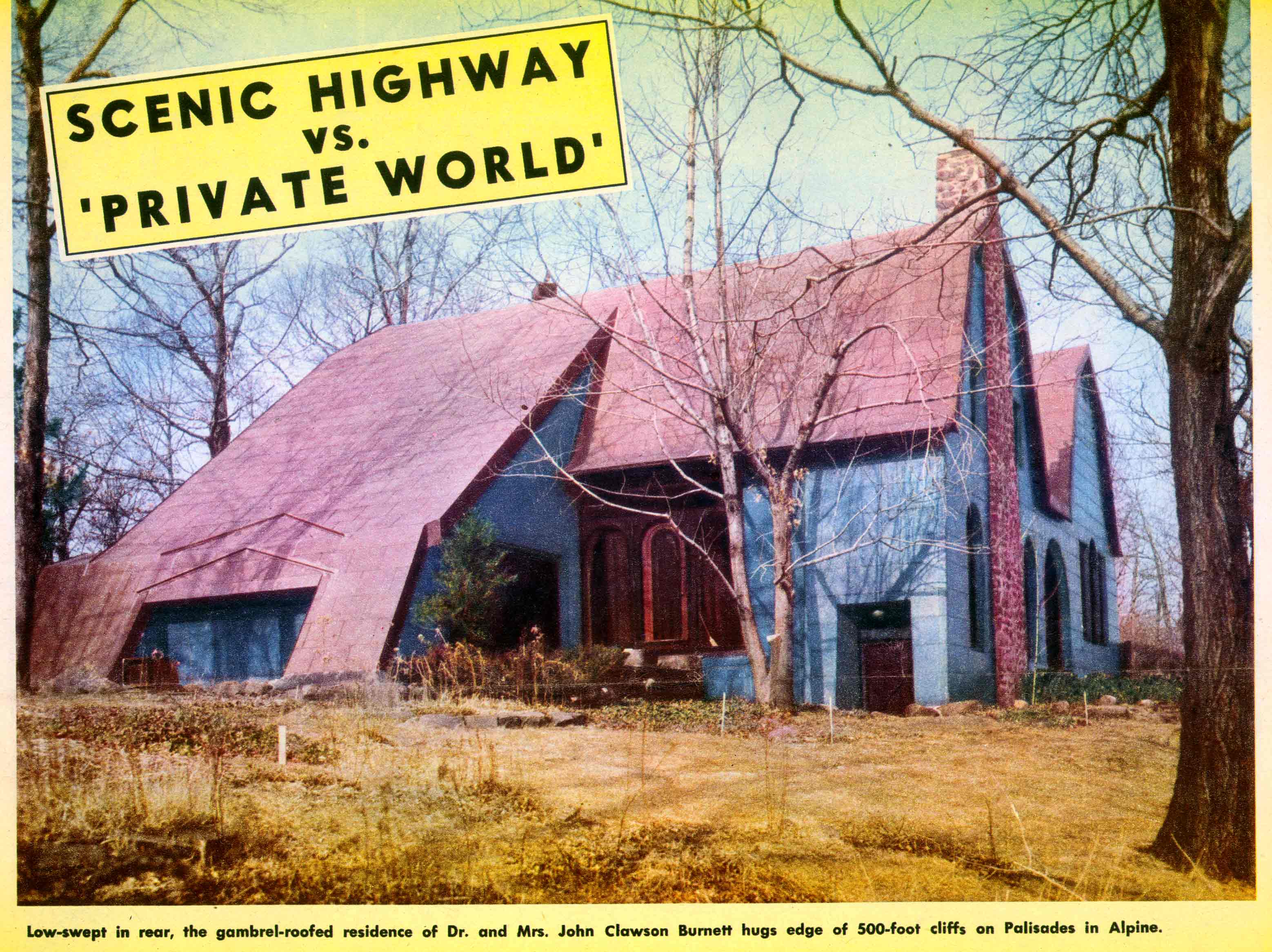

Photos taken of the Burnett estate shortly before demolition.

Photos: PIPC arcives.

They came in the early 1920s: John Clawson Burnett, a young osteopath and scientist; Cora Timken, an artist and sculptor, some years his senior and an heiress to the vast Timken roller-bearing fortune. The story goes that they camped at the site for their honeymoon, as they drew their plans to shape a private world high atop the lofty cliffs.

She designed all of the buildings, crafting them to fit the contours of the stone-swept landscape. Their residence, faced in green terra-cotta tiles, stood on the very cliff edge, plate glass windows offering a panoramic sweep of the Hudson. It was built around two live trees, whose branches spread above the graceful double-curves of the roof.

Many yards distant, in the woods, was the dining hall, with a two-story upswept roof at one end to house a pipe organ that could mechanically play from rolls of music.

For her husband, sited even more distant in the woods, was the copper-roofed laboratory where he experimented with the healing properties of electromagnetism. He believed he might find a cure for all of mankind’s ailments here, and the lab was constructed using no magnetic substances that might interfere with this work.

For her, a pair of “igloo”-like studios set on distant outcrops of the escarpment, attainable only by rugged trails that skirted steep ravines. Other outbuildings — a guard house and a sprawling, U-shaped garage structure — were scattered across the more than fifty acres they owned. For the larger buildings, she designed curved corner columns that came to flared bases. Around the bases, large stones were set, to give the appearance of “elephant’s feet.” Complementing the animal motif, just west of the residence was a swimming pool, lined with rock and shaped like a coiled serpent.

Around it all was strung a sturdy chain-link fence topped with barbed wire. Guards patrolled the grounds, accompanied by dogs.

She filled the buildings — even the grounds — with art, much of it from the East. Into the manor house, with its two living tree trunks, the contents of an entire Indian temple were carefully unpacked. Egyptian statuary — birdlike gods and totems — stood sentinel along the pathways between the buildings.

Even Dr. Burnett’s laboratory housed part of their extensive collection — a factor that only added to the tragedy of the early morning hours of March 12, 1939, when a fire destroyed the lab and all its contents. For years after, the lab remained in the woods, a burnt-out husk. But the Burnetts kept to their cliff-top lair.

She cultivated a reputation for philanthropy, donating to art museums and the like. He became an active member of the Alpine community, giving generously to the town’s police and fire services. During World War II, he served as the town’s Civil Defense director.

He also made plans to assure his and Cora’s own defense in a volatile and war-ridden world. Eighteen workmen were contracted to construct a vast bomb shelter beneath the residence, hewn by hand (dynamite, of course, was unthinkable here) from the dense diabase beneath the house. The shelter was to be a hundred feet long — more than adequate to house the Burnetts and their art collections.

But changes in the post-war world presented, in hindsight, a greater threat to the life they cherished than bombs ever would. The United States entered upon a spate of post-war highway building, and ground was broken for the Palisades Interstate Parkway, to run from the George Washington Bridge to Bear Mountain, New York — and straight through the heart of the Burnetts’ unnamed estate.

A lengthy and acrimonious legal battle ensued. In the end, the government prevailed.

Cora Timken Burnett died in 1956. In 1957, a condemnation award of $1,585,000 was offered to Dr. Burnett — for an estate he and his wife had maintained could never be given a dollar value. It could only exist precisely where it existed. In October of 1959, Dr. Burnett followed his wife, at the age of 72. A month later, a bid of $29,600 was accepted to raze the estate.

A section of chain link fence still runs beside U.S. Route 9W. Just off the Long Path, hikers still find the swimming pool, now filled in, trees growing from within it. Beneath the hikers’ boots are buried the massive water pipes that led to three 75,000-gallon cisterns that supplied the needs of the estate (but not enough to save the lab). Also beneath their boots, presumably, is an unfinished bomb shelter.

Initially, one or two of the buildings, with their “elephant’s feet,” were left standing, to be used as Parkway maintenance facilities. That plan was abandoned and those buildings, too, were demolished. Before their destruction, though, hikers would occasionally stumble upon them.

Three decades later, one of those hikers would write an article about his “weird” discovery.

– Eric Nelsen –