Gray Crag

A “Cliff Notes” Story

June 2010

Heading north from Park Headquarters on the Long Path, about a half mile in, signs begin to appear that this was not always the mature forest that it is today. A piece of metal pipe pokes up from the trail; a row of trees grows in a suspiciously straight line; wooden fence posts, shrouded in bushes, mark what might have been a pen for an animal.

An unmarked side path meanders toward the cliff edge and, when it gets there, meets with a concrete bridge span, about thirty feet long and supported by a pair of steel I-beams. It crosses to a free-standing pillar of rock that forms a tabletop, about two hundred feet long, but only a dozen or so wide. Most hikers pause at the bridge; put a toe on the aging concrete, calculate the depth of the chasm beneath it — thirty feet? fifty? — and — maybe — cross over it, some in a quick rush, others in deliberate steps. Forest shadows meet open sun; poison ivy grows in thick shocks from cracks in the rocks. The Hudson glimmers more than forty stories below, Yonkers sprawls against the far shore, Long Island Sound glints in the distance. This is “Gray Crag” — both the unique rock formation with its unexpected bridge, and the grand estate that once occupied the grounds here.

It was in 1918 that John Ringling (yes, that Ringing) and his wife Mable (née Burton) bought two big properties here and merged them into the hundred-acre estate they named Gray Crag. It would serve as their summer home through the 1920s, while they kept their place in Manhattan and began to build an even grander estate in Sarasota, Florida.

John Nicholas Ringling had made his fortune in the circus business with his four eponymous brothers (of seven brothers in all). They began in the 1880s, producing wagon shows in their native Midwest, each brother adding a particular talent — leading the band, riding horseback — to the operation. But it was when they took the show to the rails, transporting the whole operation by train, that John’s particular genius became most evident. In a day when most any small town in America could be reached by train from most any other small town in America, it was John who specialized in the confounding logistics of moving thousands of square yards of canvas tent, hundreds of animals and human performers, countless stage hands and carpenters and blacksmiths and cooks and all the rest as the circus remained in constant movement for months at a time. Yet even that was only part of the story: weeks — months sometimes — before the circus came to a town, men would arrive with bills to post; then feed needed to be bought for the animals, local kids hired to help raise the tent for the big day (they were paid in circus tickets, of course), and so on. In winter, the circus and its performers rested — and John Ringling traveled the world, seeking out new acts to add to what was to become “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

For all his traveling the world over, it was in New Jersey in 1905 — in his thirties and a lifelong bachelor till then — that John met and married Mable. It was around this time, too, that his attention was moving from the circus and into other realms of business. Together, he and Mable became avid collectors of fine art. He delved into real estate, concentrating on the area around Sarasota, where he had established the circus’s winter quarters. There they built galleries for their art collection and Ca’ d’Zan, a residence fashioned after a Venetian palace.

And for around a decade they kept a summer place on the Palisades.

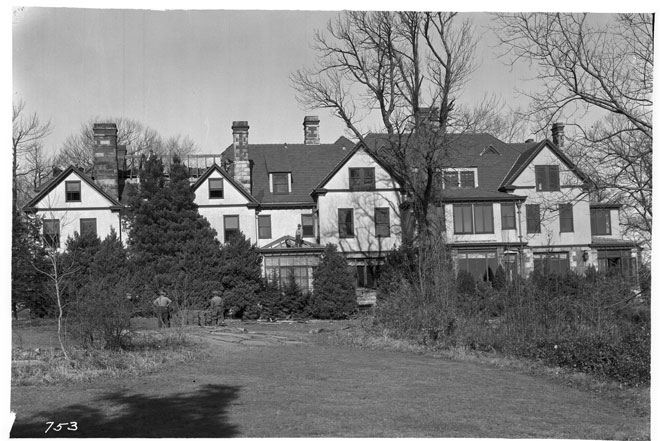

Cross back over that concrete bridge — back in the day, the I-beams and concrete were covered in a wooden veneer to make it look and feel like a rustic bridge, maybe plucked from the Alps — and look into the brush just south of it. Severed plumbing and broken bricks and tiles mark the sunken remains of the twenty-room manor house, made of stucco and stone, John and Mable had built for them here. A sales brochure from after they left listed an electric pipe organ “installed at a cost of around $50,000,” an “elevator to provide for your comfort and convenience,” and a “large master bedroom with two large tile baths.” On the grounds were a “garage, stables, greenhouse, two cottages, etc. … within 50 minutes’ drive by motor from Times Square or Wall Street…” (It would all be torn down when the Palisades Interstate Parkway was built.)

The Ringlings were famous for their entertaining. All these years later in Alpine, one can still come upon stories, only a generation or two removed from their tellers, of the circus parties the Ringlings hosted at Gray Crag, how they would hire the Yonkers Ferry to bring the whole troupe over the river for a weekend’s revelry on the cliffs. (Something to think about amidst the bird song on Gray Crag, the Hudson flowing all that way below your hiking boots: acrobats and circus performers coming across the bridge to play…)

Mable died in 1929 — just as Ca’ d’Zan was completed, the same year the stock market crashed; in every sense, John’s fortunes would plummet. He made a series of misguided business decisions. He remarried, badly, and faced a ruinous divorce trial. Finally, he followed Mable in 1936.

Today, the Ringlings’ estate in Sarasota is open to the public as the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art. (Their Alpine estate, Gray Crag, too, is open to the public, though in a somewhat different sense.)

– Eric Nelsen & Lindsey Foschini-Stabile –

Before & after: The pictures below compare photographs of Gray Crag in 1920 with photographs taken at the same locations in 2010. The historic photographs are courtesy of Carole Harris of Brooklyn, whose grandmother, Wilma Lois Roberts, of Ardmore, Oklahoma, was a teenage friend of Dulcy (Burton) Schueler, sister of Mable Ringling. In August 1920 Wilma was invited to travel east to visit the Burton sisters at Gray Crag. Present-day photos by Anthony Taranto.