In the Shade of the Cliffs

A “Cliff Notes” Story

October 2017

By 1920 they could see that they would need another bathing beach. In a few short summers the crowds pouring into Hazard’s Landing at Fort Lee had filled the beaches there to overflowing. So the Commissioners looked upriver to Englewood Cliffs, to a stretch of shoreline a little over half a mile north from the Dyckman ferry landing (“within easy walking distance…”). They named the site “Undercliff,” and they asked the legislature for $50,000 to build another big stone bathhouse there, a sister for the one they built just a couple of years before at Hazard’s.

“Undercliff” comprised a few dozen acres of forested talus between the Palisades and the river. It would have been a rough place to try to build their new facility — had several generations of Hudson River men and their wives not already subdued it.

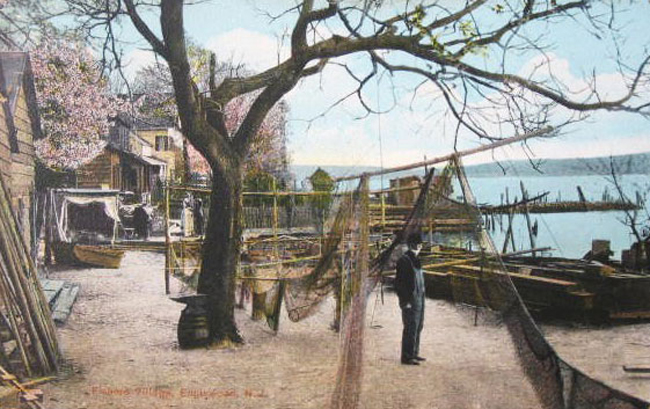

The families who’d come to live there — the Van Wagoners and the Crums, the Bloomers and the Westervelts, the Allisons — called it “Fishermen’s Village.” They cleared the talus to build neat little houses, each with its own garden. They chipped in to hire the teacher for a one-room schoolhouse for their children to rebel against, and they bent their backs to build the docks from which their sloops and periaugers sailed the green waters from Haverstraw to Brooklyn, decks piled with bricks and traprock and hay. Each spring, whatever else he might do for the rest of his year, every man among them became a shad fisherman for a month or so. At the start of the new century, even as they sold their land to the Commissioners, a handful of them stayed around.

And some stayed longer still. Buried in the deed for one large tract, amid all the usual legal boilerplate — the “metes and bounds” delineating the property — was a clause “EXCEPTING however therefrom the graveyard in the centre thereof.…”

In 1916, the year old Mrs. Crum died, one of the Commissioners recorded the story of that graveyard, as “old residents of the district” had told it to him:

I am told that the graveyard has been in existence for one hundred and fifty years, the first owner being Capt. Becker in whose family it remained for two generations, after which it was turned over to a family by the name of Wiley. The graveyard then became known as Aunty Wiley’s graveyard. The Wiley family turned it over to the wife of John Crum who was a sister of its former owner.

Ann Crum was around eighty the summer she died. She was the widow of Andrew Jackson Crum (the brother of John Crum), who in 1863 had bought around an acre of Hudson riverfront from George Bloomer for $150. There he built the house where and he and Ann raised their sons, Archie and Luther. Andrew Crum died in 1893. Neither son married.

Mother and sons sold their acre to the Commissioners for $1,200 in 1904, and then they rented their house back from them for three dollars a month, $18 payable twice a year, in January and July. The boys laid their mother to rest at the old graveyard (the second-to-last known burial there). Then they gave up the house, and Archie (who was also called “Archer” or “Archibald” or “Buck”) and Luther (who was also called “Louis,” or just “Lou”) made a go of it living off their boats on the water.

The new bathhouse opened for the summer of 1922. It was 183 feet long and 49 feet wide. Upstairs was an open-air pavilion. The lower floor had changing rooms and “shower baths” and two thousand lockers that could be rented. It was a wet, cool summer, and the crowds stayed away that first year. Then 1924 saw a typhoid scare in the park. After that, though, the crowds came — almost fifteen thousand in 1925, more each year after. (Roughly half preferred the free dressing rooms over the lockers: “Those bathing free,” the Commissioners explained in 1927, “[are] mostly women and children coming to the Park on weekdays with little, if any money to spend, willing to watch over their few belongings and so save the ten cent locker charge. Needless to say the Commissioners are only too willing to forgo the collection of a charge from such people…”) They expanded the space for “automobilists” to park up the slope from the beach, added picnic tables and grills, and ran a six-inch water main along the shore from the ferry landing.

In 1929 they razed “the old Sage house,” the last of the “Fishermen’s Village” houses. The Great Depression began that winter. For the next several years, beach attendance soared. Yet at the same time, with the opening of the George Washington Bridge, ferry revenues dropped. To help recoup those losses, the Commissioners began to charge a ten-cent beach admission to those over twelve years old; they fenced off the bathing areas to collect it. Then, for a host of reasons, beach attendance began to drop. After the 1940 season, they closed Undercliff Beach, and they ordered the bathhouse boarded up.

In July 1924, the Commissioners wrote to the superintendent at Englewood that “the question has come up as to whether Archie A. Crum, recently deceased, can be buried in the Crum family burying ground under the Palisades.” They had determined that it was within the family’s rights. “Therefore,” they wrote, “you may let the burial proceed.”

A 1967 newspaper article, “The Fishing Village That Quietly Faded Away,” had an account of the burial:

Lieutenant William Luthin, a veteran of 42 years with the Palisades Interstate Park Police, clearly remembers the last burial in the small plot overlooking the river. It was in 1924 and the funeral was that of Archer (Buck) Crum … who Luthin says was “a real giant of a man.”

The coffin was brought down to the Dyckman Street Ferry, placed on two shad barges with poles laid across them and towed by a launch of the Interstate Park Commission to a point along the Hudson nearest the burial ground.

“The family, pallbearers, and minister were taken to the cemetery in automobiles along the river drive, which was an unimproved road in those days,” said Luthin.

“The funeral procession walked down to the edge of the shore, formed into proper order and, with the minister leading, accompanied the coffin up the steep slope to its final resting place.”

Lou Crum fell in the river in 1933 and was presumed drowned. His body was never found. In 1980 the Undercliff bathhouse was gutted, leaving only its dark stone walls and a pair of wide stairways that just end.

– Eric Nelsen –