“And Wrestled with the Glaciers”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

March 2009

Indeed does not the real history of the whole world repeat itself anew each day?

Van Dearing Perrine, 1903

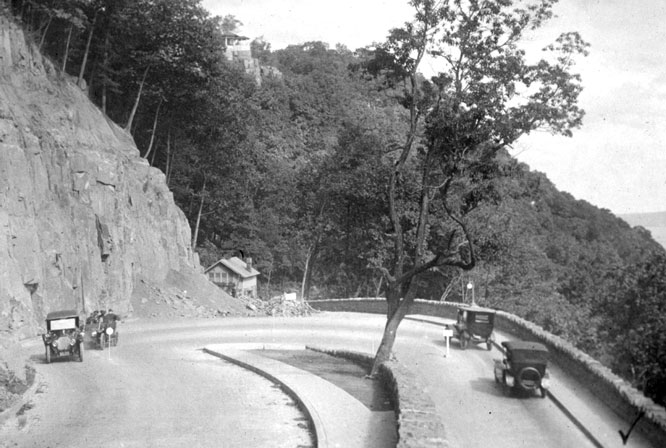

This September we will mark the centennial of the formal dedication of the Palisades Interstate Park, which was held in 1909 at the “Old Cornwallis Headquarters at Alpine Landing” (what we today call the Kearney House). So what was it like here in 1909, in a brand new park? In this story, we tell the tale of a man who, though mostly forgotten today, was in 1909 a rather well-known resident of the Palisades, the painter Van Dearing Perrine. (It bears mentioning that in the early years of the park quite a few people still lived in houses along the riverfront. Some were year-round residents, descended from settlers who first built those homes, working the river as boatmen and fishermen. Others were “city folk” who rented houses for summer cottages. Perrine was neither: as far as we can tell, he was the sole winter-only resident of the park…)

He was born on the plains of Kansas in 1869 and played under the wide sky and had a dog named Fido. His father, a Union Army veteran, died when Van Dearing Perrine was seven, his mother when he was twelve. Another family took him in for a while at Fort Scott and sent him to school. He learned that he could draw. From his teens into his twenties he rode the rails, a hobo, working odd jobs, plastering walls here and there (he had learned the trade from his older brother), was a cowboy on a cattle drive in Texas. He drew. He heard of Cooper Union, that it was a free art school. He peeled potatoes on a steamer from Galveston to New York City. He took some classes and worked around.

He ended up for a time living in a simple house he’d helped build in Ridgefield, in the Jersey countryside, where he trundled about in a pair of wooden clogs he bought from the old Dutch brick makers on the Hackensack. He kept a pistol and a cat he named Mitzi. With a group of artist friends he helped form the “Country Sketch Club,” sometimes meeting around the fire in Ridgefield, sometimes on Broadway in the City. In 1898 the National Academy hung a painting of his, a scene of Ridgefield in winter. He was at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901 when President McKinley was shot. Back in New York, crossing the Hudson by oar, he explored the Palisades.

He fixed up an abandoned one-room quarryman’s shack and got to know some of the folk still living along the river in the new Interstate Park — Mrs. Crum and her “boys,” Art and Buck, her bachelor sons — “Captain John” Van Wagoner and his wife, “Aunt Frank.” He discovered hidden crevasses and secret caves. He watched storms sweep down the river to wrack the tall cliffs — and woke to crystal mornings in their wake. He met Mary Bacon Ford, a patroness of the arts, and that led to an exhibition at Glaenzer’s in May ’03 — where his works fetched over a thousand dollars.

He went to Europe the first time that summer.

Back in New Jersey: The Commissioners agreed to let him lease an old schoolhouse on its grounds in Englewood Cliffs, halfway up the crude road from the Englewood Dock. He lovingly fixed it up, made it his winter home-cum-studio. He sketched the local people, the trees. The cliffs. With a visiting friend he braved the cold late one afternoon to get groceries in Englewood; the two of them bent into the wind on the old road as they trudged back, their supplies over their shoulders in sacks, the snow, the cliffs above, the river beyond: an image too striking not to commit to canvas (and then, remembering how they had paid the grocer with only an I.O.U., with a wink he gave the dramatic-looking painting an equally dramatic title). He submitted “The Robbers” to the Carnegie Institute’s 1903 art show. That fall it won Honorable Mention.

He became known as the “Painter of the Palisades,” the “Thoreau of the Palisades.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, discussing painters in April 1904, described him as “one of the strongest Americans we have.” Theodore Roosevelt — who had ridden and hunted along the tall cliffs as a youth and had been their champion while governor of New York — purchased one of Van Perrine’s paintings of the Palisades to have it hung in the White House.

He’d spend the warm months of the year elsewhere, Long Island was a favorite, someplace he could plant a garden. He’d return to his schoolhouse on the Palisades after the leaves had fallen, so that his painter’s eye could probe the raw contours of the rock faces. To a friend he wrote of the cliffs: “Their bigness — immensity — ruggedness appealed to something in my own nature. I tried to use the cliffs as symbols of the vast stubborn struggle of life, the immense grind, the immense upheaval, the eternal and silent combat that is typified by these crags that have pitted themselves against the elements and wrestled with the glaciers.”

In November 1908 he returned to the Palisades to find the schoolhouse had burned that very morning, its ruined stone walls still warm, his sketches, his notes — ashes. Heartsick, he moved into an abandoned five-room house next to Captain John and Aunt Frank’s.

Through much of 1909, then, the year of the park’s dedication, the “Painter of the Palisades” would be working anxiously with the Commission to draw up plans to rebuild the schoolhouse, to restore it to exactly what it had been — and yet to make it somehow even better than it was. (One can sense a whiff of exasperation — perhaps — in the close of a letter from the Commission’s secretary to a contractor who was bidding on the project: “I might add that Mr. Perrine has at his residence at Englewood Cliffs a wax model of the building which he will be very glad to show you.”)

In October 1909 Van Dearing Perrine would be plastering his new studio walls.

He married Theodora Snow in 1911. They would have a son and a daughter, the family spending their winters in the Palisades through 1923. His later work included the development of an innovative program of art instruction for children. He published a book on the topic, Let the Child Draw, in 1936; Eleanor Roosevelt asked him to the White House to discuss it. Van Dearing Perrine died in 1955 at the age of eighty-six.

– Eric Nelsen –