Fire on the Mountain

A “Cliff Notes” Story

June 1998

With the recent success of a certain major motion picture, we felt we’d put in our own idea for a disaster tale set amid the luxuries of a bygone era. (Lacking three hours to play with — let alone a multi-million-dollar budget — we’ve had to drop our fictionalized love story. Reluctantly.)

As shadows overtake the tall cliffs on the late spring evening of Tuesday, June 3, 1884, the tired workers of the Palisades Mountain House retire to their top-floor quarters for a well-earned rest. The housekeeper, Miss Enwright, has helped manage this staff of “thirty-five male and female servants” during the endless preparations for the new season, now just a week away.

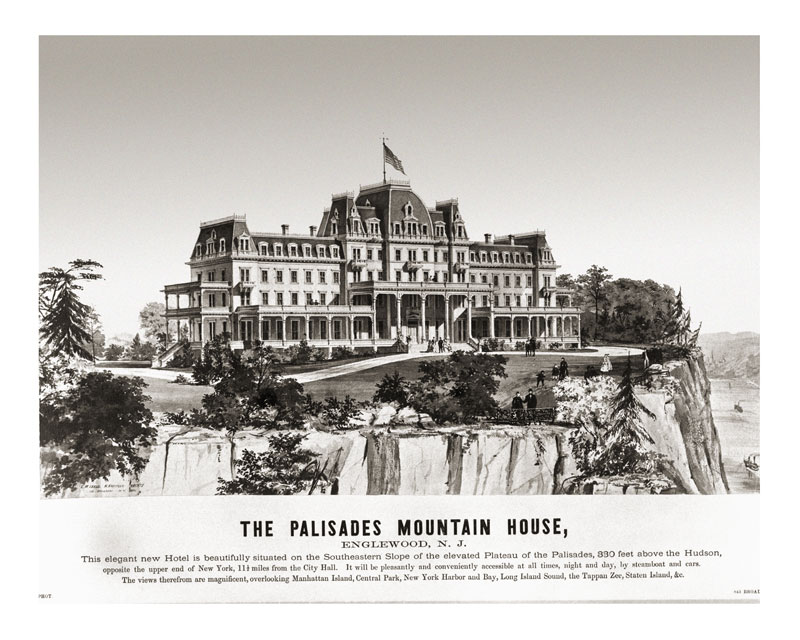

The hotel belongs to a venerable tradition of “country resorts” and basks in its reputation as one of the finest among those on the western Hudson. Set on the very brow of the Palisades, more than 300 feet above the river, the gargantuan wooden structure — 600 feet long and five stories tall — has just been treated to a fresh coat of paint, inside and out, from its grand entranceway to the top of its cupola. She offers only the finest in amenities to the well-heeled vacationer, with “a telegraph office, billiard hall, bowling alley, barber shop, cigar stand, reading rooms, public and private parlors, and reception rooms.”

It is to be the Mountain House’s thirteenth season*, and a hundred rooms have already been engaged — though the resort can accommodate up to five hundred guests at a time. Many of these guests will arrive from New York City by steamboat. After landing at a private dock at the foot of the cliffs, they will take a stagecoach up a spectacular, winding road “cut out of the face of the rock at great expense” by the builders of the Mountain House (this road is the forebear of Dyckman Hill Road, the park’s Englewood Cliffs entrance). Others will come on the Northern Railroad, then stage from Englewood. Either way, hardly an hour after departing the city, they will find themselves in another world. The hotel boasts of “the completeness of its appointments, the salubrity of the air, the grandeur of the views…” (“Salubrity” is an important motif in nineteenth-century resort advertising, as many guests come for respite from the diseases of the cities. “It is not venturing too much to say,” the Times will nonetheless venture, “that there is not a place within many miles of New-York City more deservedly held in repute for its healthfulness than the valley through which the Northern Railroad runs. … It is especially beneficial to consumptives … and the dyspeptic will rarely fail to reap immediate benefits…”) For the more vigorous, horses are stabled, with which to explore miles of rustic lanes, and boats can be rented for the river. “Some sport, too,” the Times will note, “may be had with dog and gun, and rod and line, more than would naturally be anticipated from the proximity of the locality to the centres of trade and commerce.”

At the helm of the resort’s complex operation is her manager, William Perry, who along with his daughter is staying in the huge, almost empty structure. With him as well this evening are the resort’s principal owner, William O. Allison, and his lessee, D. C. Hammond, and the latter’s father. As they drift off to sleep that evening, neither staff nor management can possibly foresee how this haven of health and sport and luxury on the mountain, in the course of two short but agonizing hours, is to turn into a waking nightmare.

On the ground floor, Miss Perry, the manager’s daughter, is the first to awaken from her sleep. At about one o’clock in the morning on Wednesday, she hears what she takes to be running water. When she investigates, she discovers to her horror that a blaze has somehow begun in the dining room at the southwest end of the building, and that the sound she’d heard was “the roaring of the flames or the dropping of cinders.” On the second floor, the junior Hammond also awakens, and in his grogginess at first thinks the sound to be workmen in the dining room. As the hallways rapidly fill with smoke, the two are able to rouse the others in the building. Most of the staff are quartered in the far north end, and are able to save themselves by the fire escapes, though it will be reported that a young bartender named Mr. Godfrey, perhaps sleeping through the first alarms, was “obliged to rush through the flames and smoke to reach the fire-escape, and he was burned about the face and hands, but not seriously.”

A “colored waiter” named only as Robert fares somewhat worse. Having escaped unhurt, he is nevertheless enlisted by the hotel’s clerk, a Mr. Vail, to return to the burning building to help retrieve the clerk’s trunk. The flames soon beat them back, and Vail is able to flee down the fire escape to safety. Robert — at that point perhaps farther into the building — cannot reach the fire escape, and so tries his luck on the burning stairway, and “his hands [are] badly burned…”

The men and women there know that the nearest fire wagon is in Englewood, too far away to be hitched to a team and drawn up the steep hill in time to help. They attempt to form a bucket brigade to a nearby well — an effort as futile as it is noble. The hotel quickly becomes a roaring, spitting inferno, and the brigade is soon forced back. Flames illuminate the cliff top like daylight, burning for almost two hours before the building finally collapses into itself. The men and women can only stand back from the heat and watch. For many, the flames will devour all their worldly belongings as they stand there, leaving them with only the nightclothes in which they escaped. While reports will say that some “cried and moaned piteously,” most will stand stock-still, numbed by the disaster. By morning’s light, little will remain for them to stare at but two blackened chimneys, twin sentinels over a scene of ashes and waste ringed by scorched trees.

The Palisades Mountain House will never be rebuilt.

The views still possess grandeur, the air, we hope, at least some of its former “salubrity” — but all traces of the grand resort are long gone. Her best evocation may be in the beautiful brick Novitiate of the Sisters of St. Joseph, built in 1939 on roughly the same site. And, yes, we’ll have to admit that our comparison to that other disaster is something of a stretch. For one thing, not a soul — thankfully — perished at the Palisades Mountain House. For another, there are no tantalizing strings of “what-ifs” to contemplate, no icebergs that might have been missed. As best we know, in fact, no cause for the fire was ever determined, though “there was nothing to indicate incendiarism.” Still, the story of the Mountain House fire does shed some interesting light (no wordplay intended) on another time period, helping capture some of its texture. And, come to think of it, there is in fact one good “what if” to bring up. What if the fire had occurred a week later, once the resort’s busy season had actually begun? Now that might have been a disaster for the history books…

And, by the way, we saved our notes for that love story. So if anyone from Hollywood happens to read this — “let’s keep in touch.”

– Eric Nelsen –

*Though some later accounts have the Mountain House opening in 1860, that date seems suspect to us: contemporary newspaper reports and advertisements all point to its being built during 1871, its doors opening the following June.